Most details about the lives they lived are lost to history, but records offer glimpses into their experiences at Carlisle.

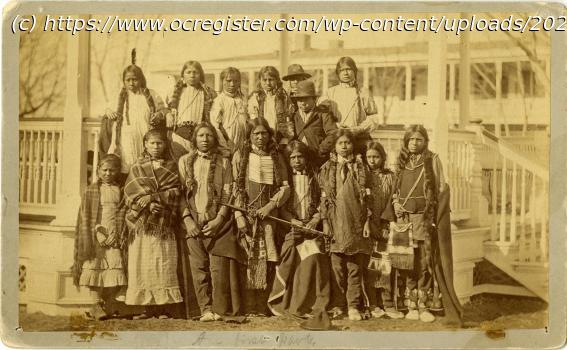

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School had not yet held its first class when Matavito Horse and Leah Road Traveler were taken there in October 1879, drafted into the U.S. government’s campaign to erase Native American tribes by wiping their children’s identities.

A few years later, Matavito, a Cheyenne boy, and Leah, an Arapaho girl, were dead.

Persistent efforts by their tribes have finally brought them home. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma received 16 of its children, exhumed from a Pennsylvania cemetery, and reburied their small wooden coffins last month in a tribal cemetery in Concho, Oklahoma. A 17th student, Wallace Perryman, was repatriated to the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma in Wewoka.

Burial ceremonies are “an important step toward justice and healing for the families and Tribal Nations impacted by the boarding school era,” the Cheyenne and Arapaho government said. Seminole communications director Mark Williams said Perryman’s family wanted no public statements.

Most details are lost to history, but records in the National Archives and documents assembled by a team at Dickinson College offer glimpses into experiences at Carlisle, where 7,800 students from more than 100 tribes were sent as the U.S. government systematically and violently evicted Native Americans from their lands to seize them for white settlers.

Among the 17 were children who tended fires, raised pigs and learned how to make clothes. Some were baptized as Christians. One earned 66 cents over four days at the school shoe shop. Another was praised for finishing three pairs of pants in one week — when he wasn’t making bricks.

Their causes of death, if mentioned in school records, include tuberculosis, spinal meningitis and typhoid fever. Perryman died after abdominal surgery. The records are often contradictory, obviously wrong about names and ages or lacking basic information about their families.This illustration shows a combination of images provided by the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. (AP/Dario Lopez-Mills)

“Sometimes the only evidence of a child’s existence is a scrap of paper with a hastily scribbled note,” said Preston McBride, a Pomona College historian who has examined boarding school death records.

Upon arrival in Carlisle, their long hair was cut. They were issued military-style uniforms and often housed apart from any relatives, forced to speak English.

In addition to lessons in reading, writing, math, science and other subjects, they were sent to work in “outings” at farms and homes.

Several of the 17 were closely related to tribal leaders, reflecting how the U.S. government used the boarding system to control Native people. Each one was somewhere between a hostage, prisoner of war and student being forced to assimilate, Harvard University historian Philip Deloria said.

“It’s undoubtedly true if you have someone’s kids you have a certain amount of leverage against them,” Deloria said.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho had been debilitated by decades of battles for their very existence by the time classes began at Carlisle. Some of their children had lost relatives in the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado and the 1868 attack on Black Kettle’s camp along the Washita River in present-day Oklahoma.

Домой

United States

USA — Science The remains and stories of Native American students are being reclaimed from...