An alleged witness to the rape attempt the Supreme Court nominee stands accused of has opined about rowdy-young-male behavior for years.

According to Christine Blasey Ford, there was one witness to Brett Kavanaugh’s attempted rape of her at a high-school party in the 1980s: Kavanaugh’s Georgetown Preparatory School classmate Mark Judge. She says he was in the bedroom where she was attacked, laughing “maniacally” with the future federal appointee, and that she was able to get free once Judge jumped on top of her and Kavanaugh.

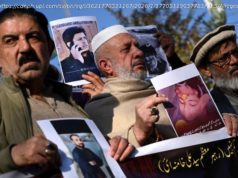

Judge has served as a character witness for Kavanaugh in recent days, denying Ford’s account and saying, “It’s just absolutely nuts. I never saw Brett act that way.” Other statements of Judge’s, though, are now also receiving attention. Like the quote he chose for his high-school yearbook page: “Certain women should be struck regularly, like gongs.” Or the article in which he wrote this: “There’s also that ambiguous middle ground, where the woman seems interested and indicates, whether verbally or not, that the man needs to prove himself to her. And if that man is any kind of man, he’ll allow himself to feel the awesome power, the wonderful beauty, of uncontrollable male passion.”

A prolific writer of articles and books, Judge’s archive is filled with stories of a rowdy adolescence and opinions about, among other things, sexual assault. That archive is now being pored over for evidence that might relate to Ford’s allegations. The Washington Post story that first named Ford mentioned Judge’s memoir, Wasted: Tales of a Gen X Drunk, which features the character Bart O’Kavanaugh, who “puked in someone’s car” and “passed out on his way back from a party.” In a 2016 lament about how social media discourages juvenile delinquency, Judge wrote, “When my high-school buddies and I got together and exchanged memories of that time, we found ourselves genuinely shocked at the stuff we got away with.”

Fondness for underage mischief making does not make for corroboration of an alleged rape attempt, and Kavanaugh is not directly implicated in any of Judge’s writings that have emerged. But reading through Judge’s work does highlight that what’s happening now—both in the Kavanaugh scandal and more broadly with the #MeToo movement—really might be a culture war. Judge served as a defender of the old-time gender mores, both as lived in the real world and as depicted in entertainment. In a 2013 piece, “ Feminism and Body Language: A Double Standard?,” he repeatedly condemned rapists, but he also seemed to lay some responsibility on women who dress provocatively. Often, he appeared to sympathize with the “boys will be boys” logic now used by some to imply that even if Ford’s story is true, Kavanaugh should still be on the Supreme Court.

Brett Kavanaugh and the revealing logic of “boys will be boys”

Much of Judge’s writings draw on pop culture from earlier, supposedly less complicated times. The aforementioned column mentioning “uncontrollable male passion” celebrated the damsel-in-distress tropes of hard-boiled crime novels, and it invoked William Hurt’s character breaking and entering in the name of sex in 1981’s Body Heat. When criticizing the late-night host John Oliver for pressing Dustin Hoffman about allegations of harassment decades ago, Judge wrote, Oliver “can’t comprehend that the world may have been different in 1985. It was, and that should be taken into account, even while calling for a morally more upright world today.” Another column: “No one wants to live with inappropriate sexual behavior. But we don’t want a world without Benny Hill, either.” (Hill’s once-ubiquitous comedy has, in fact, diminished in public memory partly due to its perceived misogyny.)

Such arguments were connected with a broader kind of nostalgia. “To view a movie like 1976’s The Bad News Bears is to witness a country where 12-year-olds smoke, drink, gamble, have adult conversations, and use language that is now banned on right-thinking college campuses,” Judge wrote. “I was 12 when The Bad News Bears came out, and remember how it stunned friends and me—not for its scandalous scenes and language, but because it was so accurate. It was us.” In his paean to juvenile delinquency, Judge wrote, “While it is a very good thing that the young are committing fewer crimes, it’s also important for adolescents to have moments of complete, anonymous freedom. It’s in that space, away from the glow of the iPhone, where kids can cultivate the darker part of their soul—that shadow part of us that is the seat of some danger, yes, but also of creativity.”

The notion that the “darker part” of teenage exploration might have lasting victims is part of what’s been asserted by Ford’s story of being attacked in high school. And Judge’s other documented viewpoints suggest that elegies for lost teenage wildness are often rooted in very specific identity politics. A 2011 column lamented the supposed lawlessness of black teens on Halloween. Another from 2013 criticized the perceived promiscuity of gay men. Some types of folks, it would seem, should be permitted license to act out their impulses, while others should not.

Kavanaugh does not have to answer for the opinions of his friend. But Judge’s writings dovetail almost eerily with the defense now being mounted of the Supreme Court nominee. “Even if true, teenagers!” tweeted Minnesota State Senator Scott Newman. Donald Trump Jr. posted an Instagram picture that compared what Ford was alleging to a boy passing a girl a note asking whether she liked him. What’s at issue right now is not only sexism, power, and the courts, but also adolescence itself—and whether it’s a sphere where boys can feel free to joke about hitting girls in the pages of their yearbook, or worse.

Домой

United States

USA — Criminal Brett Kavanaugh, Mark Judge, and the Romanticizing of Teenage Indiscretion