Beijing’s forays in the Middle East present Washington with a test—and an opportunity.

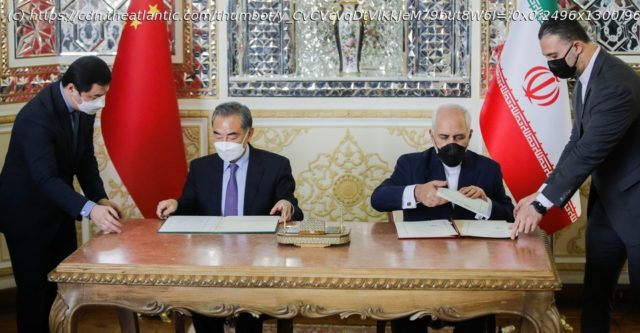

S ince taking office, President Joe Biden has talked repeatedly about competition with China. To fight off Beijing and other autocracies, he has said, democracies must uphold their values. He has talked much less about the Middle East in that time, and although he has never phrased it in so many words, Biden appears to be trying to deprioritize a region that he believes has consumed too much of America’s attention and resources. But the competition between the United States and China does not exist in a vacuum, nor is it fenced off within Asia; it is global. In the Middle East, whether it be over China’s infrastructure spending via the Belt and Road Initiative, its thirst for oil, or its cozying up to autocracies and foes of America, the battle between Washington and Beijing is fast playing out. Biden should consider how his foreign-policy priorities—China and democracy—connect in the Middle East, and why pulling too far away from the region could undermine his work on the international stage. This has become even more urgent and difficult in the aftermath of the damaging images of the chaotic American withdrawal from Afghanistan, and the doubts the debacle has cast over the Biden administration’s commitment to values and international engagement. Headlines about China signing a multibillion-dollar investment-and-trade deal with Iran, or courting Saudi Arabia to maintain access to oil, prompt questions in the Middle East about whether working more with China could benefit the region, and what that would mean for American influence. Yet these discussions remain somewhat superficial—a debate about geopolitics divorced from daily life. Until, that is, sitting in Beirut, one begins to ask how these apparent investments sit alongside stories about Uyghur internment camps in China’s Xinjiang province and the sophisticated surveillance system the Muslim minority group lives under, or why countries that purport to defend the interests of Muslims—Saudi Arabia, Iran, the United Arab Emirates—have remained silent about China’s treatment of those Muslims. China’s growing presence in the Middle East then takes on an ominous immediacy. What surveillance technology is China already selling to autocracies in the region, America’s friends among them, as it has in Iran? Who are the next candidates for a China-style social-credit system? Are some sections of the population in the Middle East the next Uyghurs? Writing in Foreign Affairs last year, Jake Sullivan, now Biden’s national security adviser, outlined what he described as “America’s opportunity in the Middle East,” arguing that diplomacy could succeed where America’s past military interventions have failed. America’s engagement with the region is typically framed squarely in military or counterterrorism terms and as a binary all-in or all-out choice. Instead, Sullivan suggested an approach relying more on “aggressive diplomacy to produce more sustainable results.” If this is what the Biden administration had envisaged for Afghanistan post-withdrawal, the approach failed at first contact. In his piece, Sullivan mentioned China only twice, in passing, as a country that was not a credible alternative to America for regional powers such as Saudi Arabia. That may miss the point: It is because of China that America has an opportunity in the Middle East—to win over the region’s people rather than simply dealing with its leaders—as well as a test, proving its commitment to values that China tramples on. U nlike America’s, China’s dealings with the Middle East are not hampered by a history of enmity with certain countries, such as the troubled relationships the U.S. has with Iran and Syria, nor is China slowed down by a legislative branch that demands accountability for foreign aid and military assistance to allies. For now, Beijing’s approach, focused on economics and devoid of lectures about democracy, has allowed it to benefit from the resources and opportunities on offer in the region, working with countries that abhor one another, such as Israel and Iran, without getting tangled up in the Middle East’s messy politics. And because Beijing has not yet gotten drawn into political dealmaking in places such as Iraq, or become mired in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, it still enjoys favorable ratings in Arab opinion polls. Meanwhile, China benefits greatly from America’s underwriting of regional security. So far, the model has worked: The Middle East is China’s largest source of oil and a strategically important region that feeds its economic growth and ambitions in Asia; in return, Beijing is able to offer ostensibly large amounts of investment.