The president said he wants global cooperation to meet challenges, but some allies and adversaries say his actions point to confrontation with China and unilateral action, belying his words.

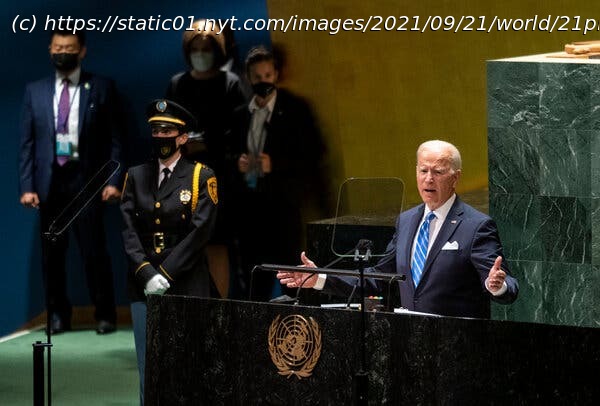

President Biden, fighting mounting doubts among America’s allies about his commitment to working with them, used his debut address to the United Nations on Tuesday to call for “relentless diplomacy” on climate change, the pandemic and efforts to blunt the expanding influence of autocratic nations like China and Russia. In a 30-minute address in the hall of the General Assembly, Mr. Biden called for a new era of global action, making the case that a summer of wildfires, excessive heat and the resurgence of the coronavirus required a new era of unity. “Our security, our prosperity and our very freedoms are interconnected, in my view as never before,” Mr. Biden said, insisting that the United States and its Western allies would remain vital partners. But he made only scant mention of the global discord his own actions have stirred, including the chaotic American retreat from Afghanistan as the Taliban retook control 20 years after they were routed. And he made no mention of his administration’s blowup with one of America’s closest allies, France, which was cast aside in a secret submarine deal with Australia to confront China’s influence in the Pacific. Those two foreign policy crises, while sharply different in nature, have led some American partners to question Mr. Biden’s commitment to empowering traditional alliances, with some publicly accusing him of perpetuating elements of former President Donald J. Trump’s “America First” approach, though wrapped in far more inclusive language. Throughout his speech, Mr. Biden never uttered the word “China,” though his efforts to redirect American competitiveness and national security policy have been built around countering Beijing’s growing influence. But he laced his discussion with a series of choices that essentially boiled down to backing democracy over autocracy, a scarcely veiled critique of both President Xi Jinping of China and Vladimir V. Putin of Russia. “We’re not seeking — say it again, we are not seeking — a new Cold War or a world divided into rigid blocs,” he said. Yet in describing what he called an “inflection point in history,” he talked about the need to choose whether new technologies would be used as “a force to empower people or deepen repression.” At one point he explicitly referred to the targeting of Uyghurs in the Xinjiang region of western China. The president’s senior aides, at least publicly, have been dismissing the idea that China and the United States, with the world’s largest economies, were dividing the world into opposing camps, seeking allies to counter each other’s influence, as America and the Soviet Union once did. The relationship with Beijing, they have argued, unlike the Cold War rivalry with Moscow, is marked by deep economic interdependence and some areas of common interests, from the climate to containing North Korea’s nuclear program. But in private, some officials concede growing similarities. The American-British deal to equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines is clearly an effort to reset the naval balance in the Pacific, as China expands its territorial claims and threatens Taiwan.

Домой

United States

USA — Political At U.N., Biden Calls for Diplomacy, not Conflict, but Some Are Skeptical