As I was driving during a cross-country road trip, my vision became wobbly. An extensive search for a specialist followed.

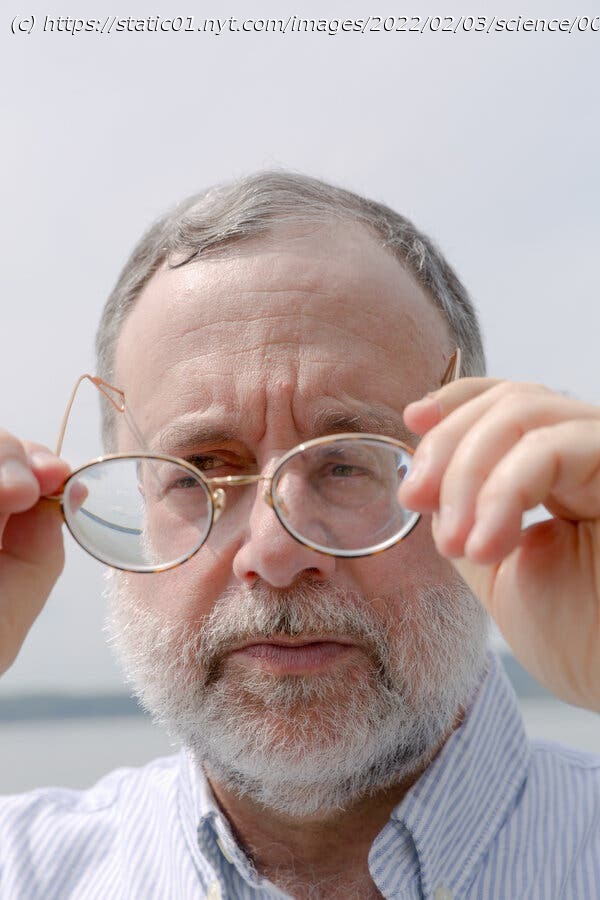

Our cross-country drive last winter from New York to Lake Tahoe was going to be eventful enough, with a pandemic, blizzards and the cancellation of salads at McDonald’s. But by Omaha, when the lanes on Interstate 80 seemed to be bouncing around before my very eyes, we entered unexpected territory. “Are you practicing your slalom turns at 80 miles an hour?” my wife asked. Road conditions were normal. Our S.U.V. had new tires. But the lanes often seemed to blur together. Sometimes the melding of lanes occurred late in the day, sometimes early. Sometimes in blinding sun, sometimes in fog. If I closed one eye, the lanes became separate again. What was happening? I’d worn glasses for nearsightedness since fifth grade; I’d seen my eye doctor within the year; my prescription was current. When we reached Tahoe, I went to an optometrist before even unpacking my skis. She said my eyes were fine, but advised an M.R.I. to rule out a brain bleed or a tumor. Days later, it did. She also told me to see a neuro-ophthalmologist, an increasingly rare subspecialty. Nationally, there are only about 600 of them, and because many do academic research or have general ophthalmic practices, just 250 of them are full-time clinicians. In six states, there are none practicing, according to a paper in the Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology last year. The Tahoe optometrist warned it could take months to obtain an appointment with one of the few practitioners in the area. But my brother, a surgeon at Stanford, helped me get an appointment at Stanford Medical Center, four hours away, in Palo Alto, Ca., the following week. Dr. Heather Moss conducted the 90-minute examination, taking measurements that included the degree to which my eyes were properly centered. My diagnosis: esotropia, which means inward turning of either or both eyes. When Dr. Moss positioned a bar of triangular plastic in front of either eye, the bouncing stopped. The piece of plastic was a set of prisms, differing in strength from top to bottom. She alternated prisms until we got it right. Wayward eyes can turn outward or upward or downward. All are forms of strabismus, and double vision is the chief symptom in adults whose brains are used to receiving two slightly differing images.