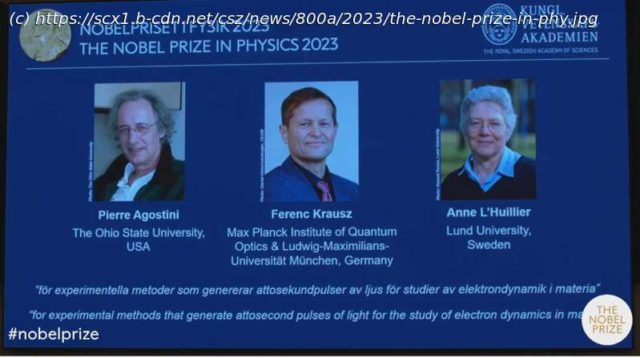

The Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier for looking at electrons in atoms during the tiniest of split seconds.

The Nobel Prize in physics has been awarded to Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier for looking at electrons in atoms during the tiniest of split seconds.

Hans Ellegren, the secretary-general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, announced the award Tuesday in Stockholm.

The Nobel Prizes carry a cash award of 11 million Swedish kronor ($1 million). The money comes from a bequest left by the prize’s creator, Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, who died in 1896.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences has decided to award the Nobel Prize in Physics 2023 to

The Ohio State University, Columbus, U.S.

Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics, Garching and Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Germany

Lund University, Sweden

«for experimental methods that generate attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter»

The three Nobel Laureates in Physics 2023 are being recognised for their experiments, which have given humanity new tools for exploring the world of electrons inside atoms and molecules. Pierre Agostini, Ferenc Krausz and Anne L’Huillier have demonstrated a way to create extremely short pulses of light that can be used to measure the rapid processes in which electrons move or change energy.

Fast-moving events flow into each other when perceived by humans, just like a film that consists of still images is perceived as continual movement. If we want to investigate really brief events, we need special technology. In the world of electrons, changes occur in a few tenths of an attosecond—an attosecond is so short that there are as many in one second as there have been seconds since the birth of the universe.

The laureates’ experiments have produced pulses of light so short that they are measured in attoseconds, thus demonstrating that these pulses can be used to provide images of processes inside atoms and molecules.

In 1987, Anne L’Huillier discovered that many different overtones of light arose when she transmitted infrared laser light through a noble gas. Each overtone is a light wave with a given number of cycles for each cycle in the laser light. They are caused by the laser light interacting with atoms in the gas; it gives some electrons extra energy that is then emitted as light. Anne L’Huillier has continued to explore this phenomenon, laying the ground for subsequent breakthroughs.

In 2001, Pierre Agostini succeeded in producing and investigating a series of consecutive light pulses, in which each pulse lasted just 250 attoseconds. At the same time, Ferenc Krausz was working with another type of experiment, one that made it possible to isolate a single light pulse that lasted 650 attoseconds.

The laureates’ contributions have enabled the investigation of processes that are so rapid they were previously impossible to follow.

«We can now open the door to the world of electrons. Attosecond physics gives us the opportunity to understand mechanisms that are governed by electrons. The next step will be utilising them,» says Eva Olsson, Chair of the Nobel Committee for Physics.

There are potential applications in many different areas. In electronics, for example, it is important to understand and control how electrons behave in a material. Attosecond pulses can also be used to identify different molecules, such as in medical diagnostics.

Through their experiments, this year’s laureates have created fashes of light that are short enough to take snapshots of electrons’ extremely rapid movements. Anne L’Huillier discovered a new effect from laser light’s interaction with atoms in a gas. Pierre Agostini and Ferenc Krausz demonstrated that this effect can be used to create shorter pulses of light than were previously possible.

A tiny hummingbird can beat its wings 80 times per second. We are only able to perceive this as a whirring sound and blurred movement. For the human senses, rapid movements blur together, and extremely short events are impossible to observe.

![This clever car charger delivers fast charging while using wired Android Auto & CarPlay [Gallery]](http://nhub.news/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/thumbab776a54817382ca42fba3ab09f42caf-238x178.jpeg)