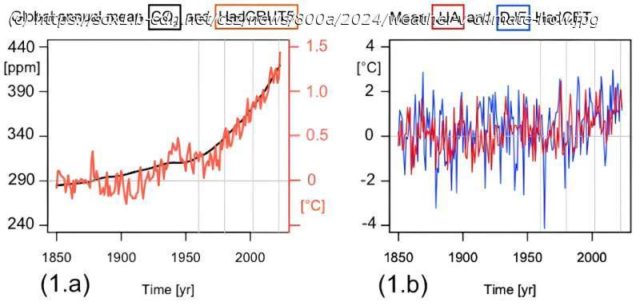

Earlier this year, the UK’s weather and climate service, the Met Office, announced average global temperatures in 2023 were 1.46°C above pre-industrial levels. This made it the hottest year on record, 0.17°C higher than the previous record in 2016.

Earlier this year, the UK’s weather and climate service, the Met Office, announced average global temperatures in 2023 were 1.46°C above pre-industrial levels. This made it the hottest year on record, 0.17°C higher than the previous record in 2016.

However, shortly after that announcement, the Met Office also forecast a multi-day blast of cold Arctic air bringing sub-zero temperatures, snow and ice to many parts of the UK. When the cold snap arrived, temperatures dropped to -14°C in the Scottish Highlands and -11°C even in England.

Ten days later, a village in the Scottish Highlands reached a balmy 19.9°C, the warmest January temperature ever recorded anywhere in the UK—by a full degree Celsius. That might seem more in keeping with the global warming trend. Yet just ten days on from that record warmth, much of the UK has again been hit by unusually cold and snowy weather.

It’s not just the UK. This winter, record-low temperatures have been observed right across Canada, the US and China.

This might seem confusing. Why are the weather and the climate producing such opposing signs? The reason is that they refer to atmospheric characteristics on substantially different timescales.

I do not think there is a person on Earth who can truly experience a «global annual average» of temperature. No one really knows what a degree of extra warmth over a century feels like, especially given temperatures might vary by 10°C between day and night in the UK, for example, or by 20°C and more between a hot summer day and a cold winter night.