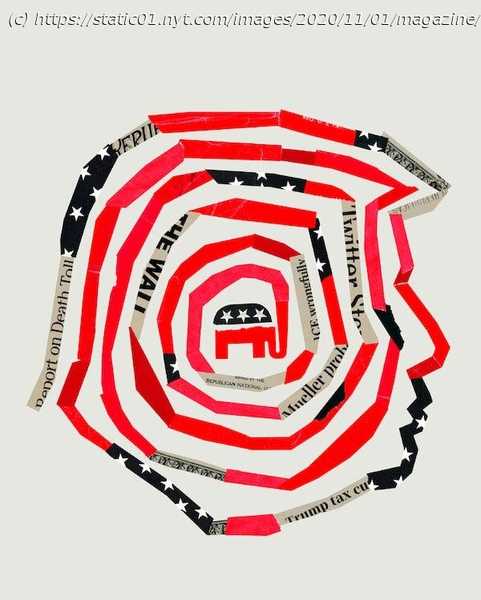

The G.O.P.’s politicians, activists and voters are still figuring out what that means.

To hear more audio stories from publishers like The New York Times, download Audm for iPhone or Android. The tourism bureau of Manatee County, population just over 400,000, advertises the expected trappings of any placid gulfside community in southwest Florida — a historic fishing village, an award-winning local library system, outlet malls. Eighty-six percent white and a noted second-home locale for retirees fleeing the Northeast in winter, Manatee has voted for every Republican presidential nominee since 1948 — the sort of homogeneity that typically produces staid politics. In the summer of 2020, as the county’s residents turned their attention to the race for District 7’s seat on the board of county commissioners, some of the hot-button issues were a new storm-water fee and the wisdom of using public funds to extend 44th Avenue East. One Republican vying for the office was George Kruse, a 45-year-old finance veteran and novice candidate who owns a commercial real estate debt fund. Kruse, who has an M.B.A. from Columbia and started his career at an affordable-housing equity fund, says he got into the race partly to address the area’s lack of affordable housing; in interviews with local media, he talked about restructuring the county budget and establishing long-term plans for sustainable growth. But from the outset his campaign included a concession to political reality. The top item on his “Conservative Principles for a Better Manatee” brochure was “Support President Trump to Keep America Great.” Kruse’s principal opponent for the Republican nomination was Ed Hunzeker, the county’s 72-year-old former administrator, who left the position in 2019 after clashing with the county commission over a controversial decision to authorize the construction of a new radio tower next to a local elementary school. In announcing his campaign, Hunzeker called himself a “strong supporter of President Trump,” and he began flooding Facebook with ad after ad to promote his affinity further (“LIKE if you support President Trump!”). Kruse did not feel his own bona fides were in question; one of the first photos posted to his campaign page showed him smiling with his arm around a cardboard cutout of Trump. Nevertheless, on June 30, he debuted his campaign’s new slogan: “Make Manatee Red Again.” “Real Conservatives in Manatee County are done with the RINO Purple/Blue wave taking over our supposedly conservative County Commission,” he declared. Three days later, Hunzeker put out an ad juxtaposing photos of himself and Trump and promising: “Ed Hunzeker Stands With Our President.” He followed up with a six-second YouTube video featuring a gentle guitar strum, Hunzeker sporting a button-down shirt and hopeful gaze and a single line of text: “Keep Manatee Great.” Two days later, a slightly perspiring Kruse filmed a Facebook Live to clarify his own allegiance. “People who know me know that I support President Trump,” he said. “They see me get out of a truck with a Trump sticker on the back. They see me walking through Publix with a Trump hat on. They see me wearing a variety of different Trump shirts. I don’t need to tell people I support the president. People just see that I support the president.” He continued: “So, you know, consider that over the weekend.” In the month that followed, it was as if Donald Trump’s Twitter feed achieved three dimensions in Manatee County. Kruse set his profile picture on Facebook to an image — a meme that previously surfaced on Donald Trump Jr.’s Instagram — of Trump’s face superimposed on George Washington’s body, with a machine gun in one arm and a bald eagle perched on the other, with a photo of Kruse himself added just outside the frame. He posted updates tracking “Lyin’ Ed’s” Facebook ad spending. Hunzeker called attention to Kruse’s small donations to Barack Obama in 2008; “George Kruse: Proud Financier of Barack Obama,” one of the ensuing ads announced. Shortly after, many in Manatee County received a text claiming Black Lives Matter had endorsed Hunzeker, who, it said, wanted to defund the police; Kruse’s campaign denied having anything to do with it. When a local group calling itself the “Trump Committee” revealed “BY POPULAR REQUEST” its endorsement of Hunzeker, Kruse’s supporters were quick to point out that these Trump supporters were not affiliated with the official Trump campaign organization. Kruse warned voters to stay vigilant against the sway of current county commissioners like Carol Whitmore, who had been vocal in her support for Hunzeker. “The inner circle, deep state of Manatee County is scrambling to close ranks,” he wrote in a Facebook post shortly before the primary in August. Kruse’s Facebook page was such a relentless barrage of wild-eyed warnings that when I reached Kruse by phone recently, I was surprised to find that he was a pretty standard-issue Republican, prone to reciting standard-issue Republican platitudes: The private sector knows best; the free market is fundamental to prosperity. His display of Trump superfandom was a rational political decision precisely because his politics were not obviously Trumplike. “I can sit here all day and say, ‘Here’s my five-step plan on work force housing,’ and a vast majority of voters aren’t going to listen to a word I say,” he told me. “But if I say, ‘I support President Trump, and the other guy doesn’t support him as much as I do,’ — well, anybody who’s going into the polling place, that’s the sentence they need to hear.” What Kruse believes that sentence communicates is not all that revolutionary in the context of Republican thought. It means that you “believe in free markets” (even if Trump himself believes in trade wars) and “a conservative approach to things” (even if Trump often seems enamored of big government). It means you’re anti-abortion and pro-gun rights. “That’s more of the Trump Republican kind of mentality,” he explained. To the extent that self-described Bob Dole Republicans still exist, they’d probably say the same thing. But Kruse said Trump’s appeal wasn’t just a set of beliefs; it was a willingness to go to extremes to pursue and defend them. “I think that’s one of the biggest differences he’s brought into the Republican Party,” he said. “It was somebody who was just willing to do what was right, even if others thought it was wrong.” Kruse and Hunzeker did not actually disagree much on what was right. In debates and interviews with local outlets, the difference between their respective pro-growth agendas came down to particulars like the value of impact fees on new development (which, Kruse now points out, they didn’t diverge on that much). But once a candidate embraced the maximalist us-or-them mode of Trump — “You have no choice but to vote for me,” Trump told rallygoers in New Hampshire in summer 2019, or else “everything’s going to be down the tubes” — no election could be less than existential. In August, Kruse beat Hunzeker in the Republican primary by nearly 15 points. His only opponent in the general election is a write-in candidate. Five days before the primary, Kruse shared an image of what appeared to be a Revolutionary War soldier on Facebook. The text on the image read: “2020 IS NO LONGER REPUBLICAN VS. DEMOCRAT. IT’S FREEDOM VERSUS TYRANNY.” “I feel the same way about our race against the inner circle, deep state of Manatee County!” Kruse wrote alongside the picture. “Don’t let Ed and Carol control your lives!” The panic and excitement attending Donald Trump have always shared an assumption: that his election marked a profound break with the American politics that came before it. During his inaugural address, as he surveyed the national landscape of “American carnage,” Trump himself invoked the advent of “a historic movement the likes of which the world has never seen before.” In the years and events that followed — the endless soap opera of the White House, the forceful separation of children from their families at the border, the pandemic, Trump’s refusal to permit even a passing interest in a peaceful transfer of power — it seemed increasingly clear that the world never had. But for all the attention paid to what Trump represents in American politics, the most salient feature of his ascent within the Republican Party might be what he doesn’t represent. When Ronald Reagan overthrew the old order of the Republican Party in the 1980 election, he did so as the figurehead of a conservative movement that had been gestating since the 1950s, with an intellectual framework that William F. Buckley Jr. had been articulating for a quarter-century, with a policy blueprint provided by the Heritage Foundation and with a campaign apparatus that quickly pivoted to the task of converting the new constituencies he’d brought into the party to a base durable enough to build on. The total merger of his movement with his party didn’t happen immediately, but the key elements of it were in place by the end of his first term, and there was not much ambiguity about what the G.O.P., if it was transforming, was transforming into. Trump’s takeover, by contrast, has been as one-dimensional as it has been total. In the space of one term, the president has co-opted virtually every power center in the Republican Party, from its congressional caucuses to its state parties, its think tanks to its political action committees. But though he has disassembled much of the old order, he has built very little in its place. “You end up with this weird paradox where he stands to haunt the G.O.P. for many years to come, but on the substance it’s like he was never even there,” said Liam Donovan, a Republican strategist. During Trump’s presidency, his party has become host to new species of fringe figures. Laura Loomer, a self-identified #ProudIslamophobe and erstwhile Infowars contributor who has been banned from Twitter and Facebook, earned presidential praise — and a campaign-trail cameo from Trump’s daughter-in-law, Lara Trump — for winning her Florida congressional district’s Republican primary in August. There is also Marjorie Taylor Greene, the party’s current nominee in the race for Georgia’s 14th district, whose embrace of the QAnon conspiracy theory and litany of racist, Islamophobic and anti-Semitic statements didn’t dissuade Trump from calling her a “future Republican star,” or Representative Kevin McCarthy, the Republicans’ leader in the House, from pledging to give her committee assignments should she win in November. But Trump’s influence is also reflected, in a more pedestrian but equally revealing way, in the ease with which George Kruse and others like him have transposed Trumplike signifiers onto otherwise utterly conventional suburban Republican platforms. Republican voters are essentially the same people who voted Republican before Trump; the party’s politicians are still mostly the same people, hiring mostly the same strategists. But their relationships to the party now flow through a single man, one who has never offered a clear vision for his political program beyond his immediate aggrandizement. Whether Trump wins or loses in November, no one else in the party’s official ranks seems to have one, either. This is a far cry from the certainty with which those same officials regarded Trump nearly five years ago. In January 2016, Republican lawmakers gathered at a harborside Marriott in Baltimore for their annual conference retreat. Paul Ryan, then the speaker of the House, would preview his “Better Way” agenda, a collection of policy proposals addressing the economy, national security, the social safety net. In scheduled sessions, members would debate the finer points of the agenda that Ryan stressed would transform the G.O.P. from an “opposition party” to a “proposition party.” And in unscheduled interludes, they would consider how their party’s presidential primary could very well come down to a contest between a reality-television star, whom they hated, and Senator Ted Cruz, whom they also hated. By the end of the retreat, many had privately agreed that the best way to achieve Ryan’s proposition-party ambitions in such a scenario was to nominate the candidate with the fewer proposals. As one Republican congressman explained to me at the time, when I was reporting on the conference for National Review Online, Cruz had his own “divisive” ideas (though in fact they were not so different from Ryan’s own). But with Trump, “there’s not a lot of meat there,” the congressman said. If Trump became the party’s candidate, he serenely predicted, he would “be looking to answer the question: ‘Where’s the beef?’ And we will have that for him.” As it turned out, Trump wasn’t especially interested in running on Ryan’s “bold conservative policy agenda.” “Put a Stop to Executive Overreach” may have been a Better Way, but Trump believed the people — his people — would be more galvanized by a ban on all Muslim travel to the United States, which he first proposed the month before. (“Offensive and unconstitutional,” Mike Pence, then the governor of Indiana, tweeted of the ban at the time.) “It’s the party’s party,” Reince Priebus, the Republican National Committee chairman, nevertheless repeatedly insisted through the summer of 2016. “The party defines the party.” It was as though Priebus and others believed the G.O.P. to be some cosmic body animated by a logic undisclosed to humankind, rather than a collection of overgrown college politicos who worked in a building opposite a restaurant called Tortilla Coast and who had lost the popular vote in five of the last six presidential elections — in other words, an institution ripe for hijacking. Paul Ryan announced his retirement 15 months into Trump’s presidency (“We are with you Paul!” Trump tweeted shortly thereafter). Kevin McCarthy, then the House majority leader, told reporters about how his wife gave him an autographed copy of “The Art of the Deal” in the late 1980s while they were dating. Priebus went to the White House with Trump as the new president’s chief of staff, only to learn via Twitter six months into the job that he had been replaced. (“We accomplished a lot together and I am proud of him!” Trump said.) The R.N.C. is now run by Ronna Romney McDaniel, Mitt Romney’s niece, who dropped the “Romney” from her name in apparent deference to Trump. As the newly inaugurated vice president, Mike Pence applauded Trump’s early executive order banning half the world’s Shiite Muslims from entering the country. This June, as Trump prepared for his second convention as the Republican presidential nominee, the party’s leaders decided to dispense with the fuss of a new platform altogether and simply readopted the 2016 platform. Never mind that the document contained some three dozen condemnations of the “current president” and “current administration” and “current occupant” of the White House; and never mind that it expressed full support for Puerto Rico’s statehood, which Trump had called an “absolute no.” Officials did, however, manage to draft a new preface: “The Republican Party,” it proclaimed, “has and will continue to enthusiastically support the president’s America-first agenda.” In Priebus’s parlance, the party had defined the party. That this is no longer Paul Ryan’s party is clear. What Trump has turned it into, though, is less so. Republican lawmakers and officials now reflexively tout their proximity to Trump — like the “100 percent Trump voting record” that Senator Kelly Loeffler of Georgia claims in a recent ad. They reference “Trumpism” casually and constantly and accede that it will in some way dictate the future of the party. But they can’t seem to agree on what it actually is. “The party right now is just Trump, right?” said one senior Senate G.O.P. aide. “So when you take him out of it, what do we have left?” When I asked even retiring or former members of Congress what the G.O.P. could be said to stand for today, few were willing to venture an answer on the record. Paul Ryan was “not doing interviews these days,” a former spokesman said. Lamar Alexander, the retiring Republican senator from Tennessee, was “more than glad to be in touch for future opportunities,” his spokesman told me. When I put the question to John Boehner, the former Republican speaker of the House, after a round of small talk, he said, “Hmm, no. I think I’ll pass on that one.” “It’s national populism and identity-politics Republicanism,” Representative Justin Amash told me, and “it’s here to stay for a while.” It was early October, and Amash, who has represented Michigan in Congress since 2011, was sitting — maskless, but across the room — in his Capitol Hill office.