It’s not legislation.

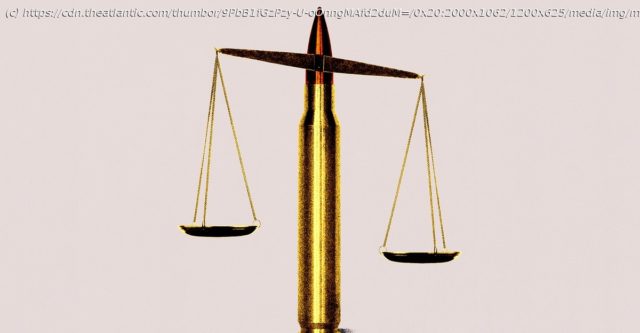

About the author: Kimberly Wehle is a law professor at the University of Baltimore. She is the author of How to Think Like a Lawyer—And Why: A Common-Sense Guide to Everyday Dilemmas and What You Need to Know about Voting—And Why. Even if Congress does manage to pass gun legislation in the weeks ahead—still a big if—that legislation will leave much to be done. The proposed framework does not, for example, increase the minimum age for purchasing firearms, address assault weapons and high-capacity ammunition, or close background-check loopholes for secondary sales, among other shortcomings. Americans who want a more far-reaching answer to the country’s gun crisis should look elsewhere: to the nation’s tort system, which is available right now to push gun manufacturers to adopt precautionary marketing practices, safer designs, and more supervised sales regimes. Since the common law of 18th-century England, tort law has existed to compensate parties for their injuries, both physical and emotional. With further gun regulation stalled in Congress and state legislatures beholden to the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Second Amendment, litigation holds out the possibility that victims of gun violence might be monetarily compensated for their injuries. What’s more, successful plaintiff-driven lawsuits can motivate defendants (and their insurers) to avoid future liability by changing their business models to maximize gun safety. In other words, the threat of litigation and high-value jury verdicts can promote self-regulation by the gun industry as an alternative to more aggressive regulatory action. Congress has made such tort suits against the gun industry difficult—too difficult—but there are still ways in, and they may be the country’s last best hope for accountability. The argument for using the tort system comes down to money. Americans lose an estimated $280 billion annually in earnings and productivity because of gun violence—and 1,131,105 years of potential life lost from gun-related deaths in 2020 alone—not to mention the hospital bills and other care-related costs incurred by those injured or disabled, including rehabilitation, medication, trauma-related therapy, testing, and home aid not otherwise covered by insurance. Gun-rights advocates argue that this is the price we must pay to protect Second Amendment freedoms, which the NRA head, Wayne LaPierre, recently called “the fundamental human right of law-abiding Americans to defend themselves.” But who should be the ones to pick up the tab? As things stand, the costs of gun violence fall unrelentingly on its victims and everyday taxpayers and consumers, many of whom may not themselves own guns. Economists refer to such side effects as negative externalities—the indirect costs of one group’s activity that are disproportionately borne by an unrelated third party, be it private individuals or society as a whole. Consider by way of example a producer of pollution. In seeking to maximize profits, it has little incentive to account for the indirect costs its pollution imposes on affected homeowners, the health-care industry, and the wider community. So long as the producer evades these costs, not only will it continue polluting, but it will overproduce. Americans bought nearly 20 million firearms in 2021, the second-highest year on record. Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, publicly traded gun manufacturers have netted $3 billion. One way to address negative externalities is for the government to intervene through subsidies, taxes, or legal constraints on the producer. But when it comes to guns, Republican legislators are overwhelmingly unwilling to take those steps. As happened with the tobacco industry, then, the most practical means of spreading the costs of gun violence is to turn to tort law and the courts. For decades after smokers with lung cancer first began suing tobacco manufacturers in the 1950s, courts mostly accepted the defendants’ arguments that smokers assumed the risk in smoking, that related cancers have other causes, and that federal laws governing tobacco advertising preempted state law, effectively insulating them from liability. Then, in 1994, a few thousand pages of the Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corporation’s internal documents were copied and leaked by an anonymous whistleblower, revealing the industry’s long-standing awareness of cigarettes’ addictive qualities.