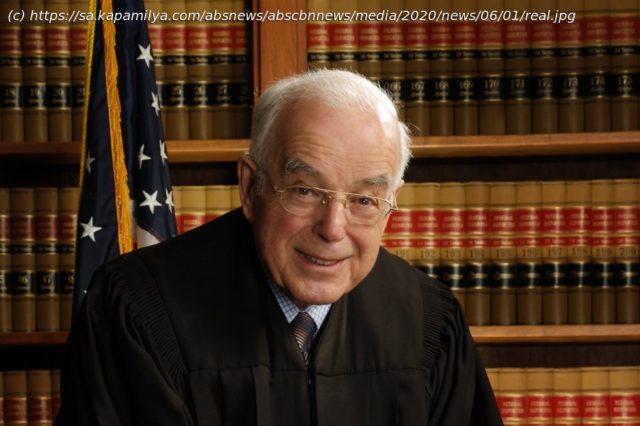

Californian Judge Manuel Real, who in 1995 ordered the Marcos family to pay martial law victims nearly $2 billion in damages, died almost unnoticed in the Philippines on June 26, 2019, five months after he celebrated his 95th birthday.

“One’s political belief is no ground for the State to torture him or to kill him.”

Judge Manuel Real, chief judge of the Los Angeles Federal Court, had this in mind like a mantra, but until after one morning in July 1989, when his superiors asked him to travel 2,000 miles away from California to Hawaii, he probably had no personal knowledge of human rights cases during martial law in the Philippines under President Ferdinand Marcos.

In an interview with ABS-CBN News, American lawyer Robert Swift remembered the Californian judge, the first to acknowledge judicially outside the Philippines through a court ruling the atrocities of the Marcos dictatorship by ordering the Marcos family to pay the martial law victims nearly US$2 billion in damages in January 1995.

Real died quietly in June last year while Swift was in Mindanao, south of the Philippine capital, distributing checks to indemnify some of the martial law victims, the fourth in a series of indemnification made possible because of Real’s rulings.

Swift remembered Real’s high regard for human lives, but until then, neither Real nor the Filipino victims had any idea that their lives would one day intertwine.

Fall of Marcos

Marcos, his wife, children and grandchildren and some 80 staff and supporters had landed in Hawaii after they were picked up from Malacanang by a US Air Force plane at the height of the military-backed, people power revolt in February 1986. They were frisked, fingerprinted, and interrogated, their suitcases full of voluminous cash and bank certificates, pieces of rare, high-end jewelry, weapons and many others all seized from a back-up plane, in what was probably the most humiliating experience for Marcos since he was tried and convicted of the September 1935 murder of Julio Nalundasan, his father’s political rival in their hometown in Ilocos Norte, north of Manila.

Marcos was served the complaints, each one a long and detailed accounts of disappearances, tortures, and executions of his critics and the looting of government coffers, two months into his exile in the paradise island.

Swift recalled the making of the complaints and how Judge Real became its central figure.

“A month into the post-EDSA euphoria, Manila was a city in transition from 20 years of virtual dictatorship,” Swift told ABS-CBN News, recalling the day he set foot on Philippines soil to meet his Filipino counterparts.

“Suddenly, there was freedom of the press. People no longer feared arrest and torture by the intelligence services. (The new president) Cory Aquino seemed to walk on water.”

Swift flew to Manila and met with Filipino lawyers Jose Mari Velez, Romeo Capulong, Rene Saguisag, and later Rod Domingo, among others. They agreed to gather the martial law victims across the country, through Selda, an organization of ex-political detainees led by activist Marie Hilao, up until they numbered 9,539, and filed the lawsuit. Hilao’s older sister, Liliosa, a student activist in 1973 was widely believed as the first murder case under martial law. Hilao gathered the victims for their affidavits.

First judge, a defeat

Real was to take the case from a colleague, Chief Judge Harold Fong of Honolulu, who had dismissed the complaints at Marcos’ plea based on State doctrine restricting an American court to rule on matters involving a foreign country, saying the “Act of State” doctrine rendered the case non-justiciable.

“During oral argument,” Swift recounted, “it was clear that Judge Fong was antagonistic to the case and dismissed it.”

But Swift, the Filipino lawyers, and the thousands of human rights victims and their families refused to lose the case, despite legal technicalities and budget constraints.

“(We) filed the case in Hawaii federal court in April 1986,” Swift said, “alleging that Marcos had orchestrated and directed torture, summary execution and disappearance against thousands of Filipinos.

A higher court reversed Fong’s dismissal on appeal, paving for Real’s entry in July 1989.

Then 61-years old, Judge Real went to Hawaii to preside over the complaints against Marcos for the crimes his family supposedly committed during his 20-year rule, mostly during the 14 years when he placed the entire Philippines under martial law.

He was seven years younger than Marcos, the most celebrated bar topnotcher in the Philippines and a close ally of the Reagan administration.

A law called Alien Tort

The Filipinos liked the idea of suing Marcos in the US, Swift said, but they had mixed feelings about getting a favorable verdict.

Swift had never met Judge Real until late in 1990 when Swift showed up in the judge’s sala to represent the victims. He remembered his first impression of his more senior fellow American lawyer.

“One of Judge Real’s strengths as a judge was his encyclopedic knowledge of the Rules of Evidence,” he said. “He listened carefully to each question posed by an attorney. Often, he struck a question even before opposing counsel could voice an objection.”

Swift would later unearth an esoteric American law, the Alien Tort Statute, also called the Alien Tort Claims Act, which reads: «The district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.»

According to a legal dictionary, tort refers to a wrongful act for which relief may be obtained in the form of damages.

First enacted in 1790, the Tort law gave US federal courts jurisdiction over cases brought by foreigners alleging violations of international law. Since 1980, courts have interpreted this statute to allow foreign citizens to seek remedies in American courts for human rights violations even outside the United States.

Not a reason to kill

Before the trial began, Swift said, Judge Real made it known that the Marcoses would not be allowed to introduce evidence that would assert that the complainants were either communists or communist sympathizers.

“The logic was simple: political beliefs and practices are not a defense to torture, summary execution or disappearance,” he said, quoting the judge.

“During the trial, the Marcos attorneys tried to question witnesses about communism. Each time, the judge struck the question and advised the jury to disregard it.”

It surprised even the prosecutors. With Judge Real at the helm, the victims saw some hope. By then, Real had been on the bench 25 years and had carved a reputation as a no-nonsense judge.

Real’s credentials

Born in 1924 in San Pedro, California, near Long Beach, Judge Real got his Bachelor of Science in 1944 from the University of Southern California and his Bachelor of Laws (LLB) from Loyola Law School in 1951, according to the website of the United States District Court for the Central District of California. He was one of the first district judges appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the Central District of California in 1966.

Judge Real was also the Central District’s longest serving chief judge, holding court from 1982 to 1993, according to the website.