One man hid Hong Kong’s multitudes better than any other.

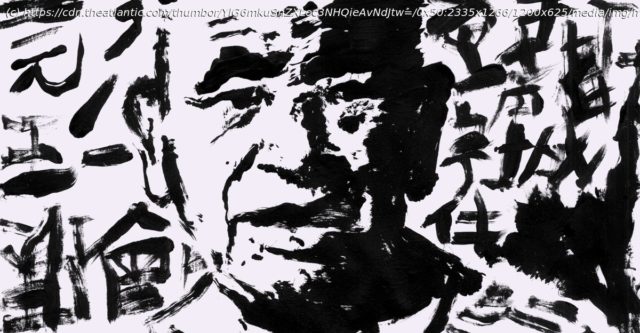

About the author: Louisa Lim is a senior lecturer at the University of Melbourne, and a former international correspondent for NPR. She is the author of Indelible City and People’s Republic of Amnesia. The mood was one of eager anticipation when, four years behind schedule, Hong Kong finally unveiled its multimillion-dollar M+ art museum in November 2021. As the docents swung open the gallery’s entrance, they revealed the very first piece in the exhibition: a pair of wooden doors daubed with misshapen, messy Chinese calligraphy in black ink. The doors had been chosen, the museum’s curator, Tina Pang, says, because they represent Hong Kong’s visual culture. Yet the graffiti on the doors is the controversial work of a man once so far outside the mainstream that he was derided by the establishment as a psychopath. This elevation to the premium spot in Hong Kong’s newest art museum caps the unlikely rise of an improbable artist who spent a lifetime railing against Hong Kong’s overlords, whether they were colonial masters from London or, later, distant rulers in Beijing. For years, I’d been obsessed with the man who had painted those wooden doors, who had become the unlikeliest of Hong Kong’s local icons. He was a mostly toothless, often shirtless, disabled trash collector with mental-health issues. His given name was Tsang Tsou-choi, but everyone called him the King of Kowloon. Over the years, Tsang had come to believe that the jutting prong of the Kowloon peninsula, adjoining mainland China and opposite the harbor from Hong Kong Island, had originally belonged to his family and had been stolen from them by the British in the 19th century. No one could say for sure why he believed this, but his conviction became a mania. In the mid-1950s, the King began a furious graffiti campaign accusing the British of stealing his land. Using a wolf-hair brush, he painted directly on the walls and slopes that he believed he’d lost, marking his domain with the art of emperors: Chinese calligraphy. His denunications took the form of tottering towers of crooked Chinese characters in which he painstakingly wrote out his entire lineage, all 21 generations of it, sometimes pairing names with the places they had lost and occasionally topping it all off with expletives like “Fuck the Queen!” When Hong Kong was handed back to China in 1997, he continued his graffiti war regardless. He was exacting in his choice of canvas; he would paint on only Crown land, or, after the change in sovereignty, government land. He gravitated toward electricity boxes and pillars, walls, and flyover struts. His words played their own magic tricks before a captive audience of haggard commuters and weary retirees; they were there one day, gone the next, washed away or painted over by an army of government cleaners in rubber boots with thin hand towels hanging from the back of their hats to serve as makeshift sunscreens. But overnight his words were back again, as if they had never disappeared, in a game of textual whack-a-mole played across the entire territory for half a century. The unbelievable thing was that the King’s stratagem worked, despite his execrable penmanship. Through his misshapen, childlike calligraphy, he became a household name, first reviled, then feted. He’d had only two years of formal schooling, and he advertised that educational deficit in every crooked character that he wrote. His writing laid bare all the flaws and idiosyncrasies a proper calligrapher would have tried to suppress, but that is what made it memorable. His words were a celebration of originality and human imperfection with a who-gives-a-fuckness about them that was genuinely inspiring. He broke all the rules. This too was a facet of Hong Kongness: The city was an in-between space, a site of transgression, a refuge where behavior not acceptable in mainland China was permitted and even celebrated. The issue of belonging has always been a complicated one for me, as a half English, half Chinese person who was born in England but brought up in Hong Kong. My family moved to Hong Kong when I was 5 so that my Singaporean father could take up a civil-service job. As far back as I can remember, Hong Kong has been my home.