4 ways in which ‘the swamp’ is doing just fine in the Trump era

«Don’t you mean drain the swamp and build the wall? » adviser Kellyanne Conway responded. Trump shot back: «No, that’s too many things. Just smush them together. »

Trump’s promise to «drain the swamp» has long hung over his transition effort — and almost always for the wrong reasons. Every time a potential conflict of interest or insider Cabinet pick crops up, there’s that pithy catchphrase looming as a contrast to what Trump is actually doing as president-elect. Newt Gingrich even said Trump’s team had exiled the slogan. (Trump has denied that ; on Tuesday, he tweeted out the slogan’s hashtag.)

Someone incorrectly stated that the phrase «DRAIN THE SWAMP» was no longer being used by me. Actually, we will always be trying to DTS.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 22, 2016

But it’s not just Trump who is now arguably «building the swamp. » On Monday night, at the 11th hour before the new Congress is sworn in, the House Republican conference voted to do something that runs pretty clearly counter to any efforts to drain their own swamp: severely undercutting the powers of an independent ethics committee set up in the aftermath of the congressional scandals of last decade.

Given this building narrative, we thought it worth recapping the ways in which the swamp is being replenished right now — or at the very least is hardly being drained.

1. The Office of Congressional Ethics

With their vote behind closed doors Monday night, House Republicans voted to do a few things :

House Republicans took this vote over the reported objections of House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) and Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.). Supporters, including chief sponsor Rep. Bob Goodlatte (R-Va.), insist it doesn’t handicap the committee’s work. But given the above, it’s hard to argue the committee didn’t lose a huge amount of power and independence. The ethics process in Congress has earned a reputation for intransigence — often because of partisanship and a desire to not rock the boat — and now members will again exercise effective veto power over their own colleagues’ ethics investigations.

Trump seemed to sympathize with the likes of Goodlatte on Tuesday, calling the office «unfair» but questioning whether its reform should have been a priority:

With all that Congress has to work on, do they really have to make the weakening of the Independent Ethics Watchdog, as unfair as it

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 3, 2017

……..may be, their number one act and priority. Focus on tax reform, healthcare and so many other things of far greater importance! #DTS

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) January 3, 2017

2. Trump’s personal finances

We still don’t know exactly what Trump will do with his personal finances as president, because he has delayed a news conference on the subject. (It’s now set for Jan. 11 .)

What we do know is that his vast business empire and foreign interests pose an unprecedented number of potential conflicts of interest for a president. And Trump doesn’t sound like he’ll go nearly as far as ethics watchdogs would like. He’s repeatedly downplayed the issue, suggesting that the media are making a big deal out of nothing.

That sounds a lot like a guy who is about to disappoint those hoping he’ll put up real walls between him and his business. And they have reason to worry; Trump has thus far indicated that he’ll put his adult children in charge of his business interests — his lawyer has labeled this a «blind trust,» but it doesn’t meet the definition — and he has continued to involve his kids in his transition effort.

Trump apparently isn’t divesting his foreign assets, either, unfurling a whole other list of potential conflicts as he deals with world leaders and foreign countries. And for the latest installment in how Trump’s business could intersect with his presidency, here’s what CNN reported Tuesday morning :

Donald Trump gave a lengthy description of his electoral victory, and lavished praise upon a Dubai business partner, during a ten-minute speech to 800 paying guests at his Florida estate Saturday night.

At points throughout his address, Trump name-checked prominent attendees, including «Hussain and the whole family,» an apparent reference to his billionaire business partner in Dubai, Hussain Sajwani .

3. Trump’s Cabinet

On the campaign trail, Trump repeatedly used Goldman Sachs as a foil — both for his top primary opponent, Ted Cruz, and for Hillary Clinton.

As of today, though, Trump has named former Goldman Sachs partner Steve Mnuchin as his treasury secretary and Goldman Sachs president and COO Gary Cohn to lead his National Economic Council. His top adviser, Stephen Bannon, also worked at Goldman early in his career. And as our Philip Bump notes , Trump’s picks for transportation secretary, education secretary, commerce secretary, deputy commerce secretary and army secretary have all worked in finance.

Oh, and he’s also assembling the richest administration in modern history , featuring six billionaires — a figure that includes Trump but doesn’t include wealthy ExxonMobil CEO and secretary of state nominee Rex Tillerson. And he’s also installed a number of elected officials to top posts, including Oklahoma Attorney General Scott Pruitt to lead the Environmental Protection Agency, Rep. Mike Pompeo (R-Kan.) to lead the CIA and Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.) to lead the Department of Health and Human Services.

Can wealthy people, those who come from the world of finance and politicians drain the swamp? Anything is possible. But Trump’s rhetoric on the campaign trail suggested he was skeptical such reform would come from Goldman Sachs or Wall Street or Congress. And for a guy who ran as a populist, his Cabinet sure looks like a collection of elites.

4. The lobbyist loophole

Shortly after Trump’s election, his transition effort put forth a plan to crack down on the influence of lobbying in his administration.

The transition team said it would ban administration officials from serving as lobbyists for five years after leaving and said state and federal lobbyists would not be allowed to serve. But some looking to serve have simply deregistered as lobbyists, meaning they technically aren’t lobbyists anymore but were just a short while ago.

The five-year ban is particularly stringent, it should be noted, and some lobbyists chose to leave the transition effort rather than deregister. But it’s still not clear what the mechanism is for preventing former administration officials from lobbying for five years. Plus, these officials can often serve as advisers to those who do lobbying in ways that don’t technically involve lobbying.

© Source: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-fix/wp/2017/01/03/4-ways-in-which-the-swamp-is-doing-just-fine-in-the-trump-era/

All rights are reserved and belongs to a source media.

More than 250 small earthquakes along the Southern California-Mexico border on New Year’s Eve have left some residents worried and scientists intrigued.

More than 250 small earthquakes along the Southern California-Mexico border on New Year’s Eve have left some residents worried and scientists intrigued.

A baggage handler was apparently locked in the cargo hold of an outbound Charlotte Douglas International flight Sunday and survived the ordeal as the plane reached altitudes of up to 27,000 feet, where outside temperatures can sink to minus 30 to 34 degrees.

A baggage handler was apparently locked in the cargo hold of an outbound Charlotte Douglas International flight Sunday and survived the ordeal as the plane reached altitudes of up to 27,000 feet, where outside temperatures can sink to minus 30 to 34 degrees.

Cleveland officials say the search for a plane carrying six people that disappeared last week over Lake Erie has resumed.

Cleveland officials say the search for a plane carrying six people that disappeared last week over Lake Erie has resumed.

(AP) House Republicans on Monday voted to eviscerate the Office of Congressional Ethics, the independent body created in 2008 to investigate allegations of misconduct by lawmakers after several bribery and corruption scandals sent members to prison.

(AP) House Republicans on Monday voted to eviscerate the Office of Congressional Ethics, the independent body created in 2008 to investigate allegations of misconduct by lawmakers after several bribery and corruption scandals sent members to prison.

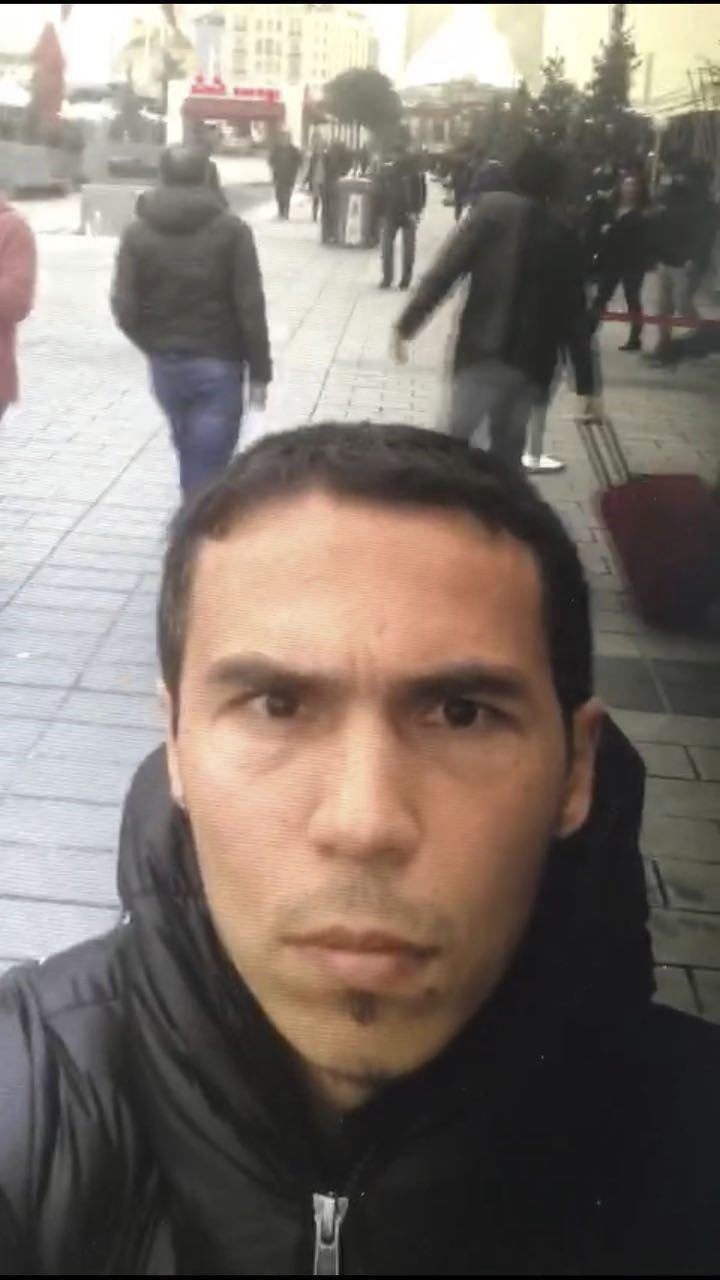

ISTANBUL (AP) — Turkish media on Tuesday ran a “selfie video” of a man they say is the gunman who killed 39 people, most of them foreigners, at an Istanbul nightclub.

ISTANBUL (AP) — Turkish media on Tuesday ran a “selfie video” of a man they say is the gunman who killed 39 people, most of them foreigners, at an Istanbul nightclub.

It described the Reina nightclub, where many foreigners as well as Turks were killed, as a gathering point for Christians celebrating their «apostate holiday». The attack, it said, was revenge for Turkish military involvement in Syria.

It described the Reina nightclub, where many foreigners as well as Turks were killed, as a gathering point for Christians celebrating their «apostate holiday». The attack, it said, was revenge for Turkish military involvement in Syria.

U. S. stock indexes are jumping on the first trading day of 2017. Energy companies are climbing with the price of oil, while banks are advancing thanks to a bump in interest rates. Those two sectors had the biggest gains in the market last year.

U. S. stock indexes are jumping on the first trading day of 2017. Energy companies are climbing with the price of oil, while banks are advancing thanks to a bump in interest rates. Those two sectors had the biggest gains in the market last year.

Former Super League champions Bradford Bulls have been liquidated after the club’s administrator rejected a bid to save the club.

Former Super League champions Bradford Bulls have been liquidated after the club’s administrator rejected a bid to save the club.