Women's March on Washington is poised to be the biggest anti-Trump demonstration

Teresa Shook never considered herself much of an activist, or someone particularly versed in feminist theory. But when the results of the presidential election became clear, the grandmother and retired attorney in Hawaii turned to Facebook and asked: What if women marched on Washington around Inauguration Day en masse?

Teresa Shook never considered herself much of an activist, or someone particularly versed in feminist theory. But when the results of the presidential election became clear, the grandmother and retired attorney in Hawaii turned to Facebook and asked: What if women marched on Washington around Inauguration Day en masse?

She asked her online friends how to create an event page, and then started one for the march she was hoping would happen.

By the time she went to bed, 40 women responded that they were in.

When she woke up, that number had exploded to 10,000.

Now, more than 100,000 people have registered their plans to attend the Women’s March on Washington in what is expected to be the largest demonstration linked to the inauguration of Donald Trump, and a focal point for activists on the left who have been energized in opposing his agenda.

Planning for the Jan. 21 march got off to a rocky start. Controversy initially flared over the name of the march, and whether it was inclusive enough of minorities, particularly African-Americans, who have felt excluded from many mainstream feminist movements.

Organizers say plans are on track, after securing a permit from D. C. police to gather 200,000 people near the Capitol at Independence Avenue and Third Street SW on the morning after Inauguration Day. Exactly how big the march will be has yet to be determined, with organizers scrambling to pull together the rest of the necessary permits and raise the $1 million to $2 million necessary to pull off a march triggered by Shook’s Facebook venting.

The march has become a catch-all for a host of liberal causes, from immigrant rights to police killings of African-Americans. But at its heart is the demand for equal rights for women after an election that saw the defeat of Democrat Hillary Clinton, the first female presidential nominee of a major party.

«We plan to make a bold and clear statement to this country on the national and local level that we will not be silent and we will not let anyone roll back the rights we have fought and struggled to get,» said Tamika Mallory, a veteran organizer and gun-control advocate who is now one of the march’s main organizers.

More than 150,000 women and men have responded on the march’s Facebook page that they plan on attending. At least 1,000 buses are headed to Washington for the march through Rally, a website that organizes buses to protests. Dozens of groups, from Planned Parenthood to the antiwar CodePink, have signed on as partners.

Organizers insist the march is not anti-Trump, even as many of the groups that have latched on to it fiercely oppose his agenda.

«Donald Trump’s election has triggered a lot of women to be more involved than they ordinarily would have been, which is ironic, because a lot of us thought a Hillary presidency would motivate women,» said Dana Brown, executive director of the Pennsylvania Center for Women in Politics at Chatham University. «A lot of women seem to be saying, ‘This is my time. I’m not going to be silent anymore. »

Boris Epshteyn, spokesman for the Trump Inaugural Committee, defended the president-elect’s popularity among women in an interview on CNN. While Trump did not receive the majority of women’s votes he got an «overwhelming» number of them, Epshteyn said.

«We’re here to hear their concerns,» he said. «We welcome them to our side as well. »

That all this could grow out of a dashed-off post from her perch nearly 5,000 miles from Washington is amazing to Shook, who has booked her ticket and plans to be in Washington on Jan. 21.

«I guess in my heart of heart I wanted it to happen, but I didn’t really think it would’ve ever gone viral,» Shook said. «I don’t even know how to go viral. »

Unsure of how to proceed those initial few days, she said she enlisted the help of the first few women who messaged her to volunteer, some of whom independently also had an idea for a march. But as the march grew in prominence, it got caught up in a broader conversation in liberal circles about race and leadership, with activists and others criticizing that initial planning group for its racial makeup: Shook said all the women, including herself, that she tapped to help in the march’s nascent stages were white.

Some also took issue with the name Shook had proposed, the Million Woman March, which was the name of a 1997 black women’s march in Philadelphia. The racial concerns set off a heated conversation on the group’s main Facebook page, with some African-American women especially taking umbrage.

For her part, Shook said her aim was not to coopt any other movement. It was just an idea that took hold after the victory of a president-elect caught on tape boasting of grabbing women’s private parts, and the defeat of a woman who seemed to her much more qualified for the job. She said she had no idea the race of the women she first contacted; in fact, she said, most had an image of Clinton as their Facebook profile photo.

Complicating matters, it became apparent that the march likely could not start at the Lincoln Memorial as Shook had proposed, since the inaugural committee has dibs on that space.

Overwhelmed and under pressure, the original organizers eventually handed the reins to a diverse group of veteran female activists from New York: Mallory, the gun-control activist; Linda Sarsour, executive director of the Arab-American Association of New York; Carmen Perez, head of Gathering for Justice, a criminal justice reform group; and Bob Bland, a fashion entrepreneur.

Together, they settled on a new name: The Women’s March on Washington, a nod to the 1963 demonstration that was a cornerstone of the Civil Rights movement. They even got the blessing of Martin Luther King Jr.’s youngest daughter, Bernice King.

In D. C., Janaye Ingram, the former executive director of Al Sharpton’s National Action Network, has been working to secure permits and hash out logistics for the march, including ensuring there is a proper sound equipment and sufficient Porta Potties.

People traveling to attend the march seem less concerned with behind-the-scenes politics than the chance to call for more family-friendly government policies, equal pay for women or reproductive rights. Some simply want to stand against the crass way Trump has spoken about women.

Lindsey Shriver, a 27-year old former pastry chef who is now an at-home mom in Ohio, said she was offended this election cycle by Trump’s rhetoric, which she characterized as «hateful and misogynistic. » She also wants to highlight the need for paid family leave and affordable child care.

«I realized that being a feminist in my own personal life wasn’t going to be enough for my daughters,» said Shriver.

Caroline Rule, 57, an attorney living in Manhattan, says she will attend with her 15-year-old daughter. While she agrees with the pro-women message behind the march, she said she’d likely participate in any march that pushed against Trump’s messages.

«I absolutely despise Donald Trump and everything he stands for,» she said.

Feminist icon Gloria Steinem has recently signed on as a march co-sponsor, and celebrities like Amy Schumer, Samantha Bee and Jessica Chastain say they plan to attend as well.

Feminist scholars say the march reflects an emerging view of feminism: That it is less defined by reproductive issues such as birth control and abortion and more about how the challenges faced by women intersect with those encountered by African-Americans, gays and immigrants.

Still, reproductive rights will be a large part of the march, with Planned Parenthood and NARAL Pro-Choice America as key partners.

Hahrie Han, a political science professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara specializing in political organizations and political engagement, said it’s not all that surprising that individual women instead of an established organization founded this march. Established organizations all come with at least some political baggage.

«The challenge with having one organization brand it as its own, is that each organization has its own image that draws some people, and pushes others back away,» she said.

© Source: http://www.chron.com/national/article/Women-s-March-on-Washington-is-poised-to-be-the-10833059.php

All rights are reserved and belongs to a source media.

The Parker Palm Springs, with its candied-colored hues of yellow and orange, was the place to be seen Tuesday morning at the Creative Impact Awards luncheon feting the 20th anniversary of Variety’s 10 Directors to Watch.

The Parker Palm Springs, with its candied-colored hues of yellow and orange, was the place to be seen Tuesday morning at the Creative Impact Awards luncheon feting the 20th anniversary of Variety’s 10 Directors to Watch.

It was nearly 10 years ago that I fell in love with Lady Gaga, through catchy pop-dance classics like “Poker Face,” “LoveGame” and “Bad Romance.” The romance continues with her soulful and visceral latest release, Joanne. I never thought I’d get to see and hear her perform the hits I’ve listened to on repeat for years, let alone up close in the luxurious Encore Theater in celebration of a new year.

It was nearly 10 years ago that I fell in love with Lady Gaga, through catchy pop-dance classics like “Poker Face,” “LoveGame” and “Bad Romance.” The romance continues with her soulful and visceral latest release, Joanne. I never thought I’d get to see and hear her perform the hits I’ve listened to on repeat for years, let alone up close in the luxurious Encore Theater in celebration of a new year.

South Korea’s finance minister on Wednesday said the government will vigorously argue Korea’s case should the U. S. make any unreasonable trade demands.

South Korea’s finance minister on Wednesday said the government will vigorously argue Korea’s case should the U. S. make any unreasonable trade demands.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 3 (UPI) — The U. S. State Department said Tuesday it does not believe Kim Jong Un has the capability to place a nuclear warhead on a ballistic missile.

WASHINGTON, Jan. 3 (UPI) — The U. S. State Department said Tuesday it does not believe Kim Jong Un has the capability to place a nuclear warhead on a ballistic missile.

— The supposed development of a long range ICBM capability by North Korea has several ramifications. Whether or not the ICBM can hit the US or not, it represents a potential catalyst for a serious regional war. Sydney — The supposed development of a long range ICBM capability by North Korea has several ramifications. Whether or not the ICBM can hit the US or not, it represents a potential catalyst for a serious regional war. At this point, the US is skeptical of North Korea’s actual capabilities. There’s some doubt as to how far this technology has advanced, and whether it can actually deliver a warhead on target. Nor are the technical issues getting any simpler: The DPRK’s stated goal of delivering nukes from submarines, particularly the obsolete and rather undersized Whiskey and The DPRK, meanwhile, is trying to get the US to reverse its current policies of non-acceptance of it as a nuclear-armed state, by developing ICBMs, real or not. As a diplomatic position, it’s a bit hard to accept the logic. It’s also potentially suicidal, for less obvious reasons. Regional detonator? The regional implications of a new ICBM capability are significant. The DPRK’s neighbors have their own views on nations with nuclear strike capacity. China has no reason to consider this new development a threat, but Japan may see things differently. Japan has reacted very negatively to short and medium range tests near its territory. Add to this the alliance between China and the DPRK, and any conflict with Japan could bring in China. That’s not a natural scenario, though. China can pick and choose its level of participation in any conflict. One way of reminding a client state that it’s a client state is to leave it hanging in a crisis. That’s not impossible, either. Nor is Russia a natural engagement. In the 1950s, Russia aided North Korea in the Korean war in many ways, including equipping its air force with the revolutionary new MIG 15s which basically rewrote air tactics for the next 50 years. It’s not clear whether the Russian Federation would respond at all in any future conflict scenario. There’s not much in it for the Russians, in terms of political or other gains. “Amused spectator” would be a likely option, unless there’s any tangible gains to be made out of a confrontation with North Korea and Western-aligned nations. A confrontation between the US and the DPRK, however, makes Chinese intervention in some forms far more likely. China has been trying to make a point about expanding its regional interests, and a Korean war might be a game changer. China’s most predictable reaction would be “not in our back yard”, with related actions, but not necessarily direct conflict. Active Chinese participation, however, could turn the conflict in to a major regional war. The more likely immediate confrontation, if any, would be a clash of the two Koreas. That could get extremely nasty, very quickly. The DPRK has what is basically a post Cold War/ Iraq War style military force, with added naval capacity. Despite the huge size of the That not very secret fact, however, could well bring in Chinese and Russian support. Currently, China and Russia provide a low level of support to the DPRK military, but the overall DPRK arsenal is circa 1980s. Against modern weapons, the viability of these systems in combat is highly debatable. That very lack of viability, however, is more of a problem than it looks in a war scenario. Given the obvious problems and serious risks in mounting a conventional attack, an unconventional attack is therefore far more likely. In 1950, the DPRK mounted a very effective surprise attack which drove the combined South Korean and US forces back to the very tip of the Korean peninsula. The current scenarios are completely different, though. Against a fully prepared opponent, a surprise attack by conventional forces would have to achieve miracles. Even with a huge force, there’s no getting away from the fact that South Korea is a very hard target for the DPRK. 1950 won’t happen again, but a variant, particularly a failed variant, could create a cascade of events, including super power involvement. No good scenarios for any Korean conflict. The most likely scenario for a real war, based on the current DPRK posture and previous actions, is a dramatic action of some kind. This would have to be a direct surprise strike, on a “no going back” basis. A serious strike would definitely bring in other nations, in different capacities. Whether the US is moving to a less engaged role or not, it has 28,000 military personnel in South Korea, and they’re potential targets either directly or as collateral damage in a strike on Seoul. Any strike on American forces, however, would instantly bring in US forces, and retaliation. The range of possible escalations is obvious. The DPRK can’t necessarily count on support in a dramatic strike, either. Starting a large scale regional war wouldn’t go down too well with China or Russia. This is no longer 1950 in other ways, too. Chinese and Russian leadership is highly pragmatic. There’s no reason to believe they’d want to be drawn in to any conflict, on any level. They are very unlikely to respond well to a sudden demand for support in a conflict with the US or Japan, or both. The degree of commitment required to support the DPRK in an actual war would be huge. Nor are they likely to enthuse about supporting the side most likely to lose in such a war. In global politics, the Koreas are a sideshow, if potentially a very ugly sideshow, if a war starts. The major powers have nothing to gain but an unwanted problem and an expensive range of options. None of those options deliver any real benefits. ICBMs or no ICBMs, the DPRK is holding one card in a game where all the other players have much stronger cards. The real risk is escalation caused by people doing the wrong things and reacting the wrong way to situations. The problem is that history is full of cases of wars starting for exactly those reasons. The development of the ICBMs has now reached at least the point at which North Korea (correct name Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) is prepared to do some gloating. While the usual pattern of information from the DPRK is based on a degree of spin, this is a bit different. When it comes to ICBMs, you either have this capacity or you don’t. So it’s likely that at least some level of increased capacity has been achieved. At this point, the US is skeptical of North Korea’s actual capabilities. There’s some doubt as to how far this technology has advanced, and whether it can actually deliver a warhead on target. Nor are the technical issues getting any simpler: The DPRK’s stated goal of delivering nukes from submarines, particularly the obsolete and rather undersized Whiskey and Romeo class subs, is of equally dubious value and almost zero combat credibility. Those subs could be tracked from one side of the Pacific to the other by Radio Shack level equipment, let alone American and Japanese ASW capabilities. A few drones could stooge around the Sea of Japan and sink them quite easily, too. Sub launched missiles really are not a working option. The DPRK, meanwhile, is trying to get the US to reverse its current policies of non-acceptance of it as a nuclear-armed state, by developing ICBMs, real or not. As a diplomatic position, it’s a bit hard to accept the logic. It’s also potentially suicidal, for less obvious reasons. The regional implications of a new ICBM capability are significant. The DPRK’s neighbors have their own views on nations with nuclear strike capacity. China has no reason to consider this new development a threat, but Japan may see things differently. Japan has reacted very negatively to short and medium range tests near its territory. Add to this the alliance between China and the DPRK, and any conflict with Japan could bring in China. That’s not a natural scenario, though. China can pick and choose its level of participation in any conflict. One way of reminding a client state that it’s a client state is to leave it hanging in a crisis. That’s not impossible, either. Nor is Russia a natural engagement. In the 1950s, Russia aided North Korea in the Korean war in many ways, including equipping its air force with the revolutionary new MIG 15s which basically rewrote air tactics for the next 50 years. It’s not clear whether the Russian Federation would respond at all in any future conflict scenario. There’s not much in it for the Russians, in terms of political or other gains. “Amused spectator” would be a likely option, unless there’s any tangible gains to be made out of a confrontation with North Korea and Western-aligned nations. A confrontation between the US and the DPRK, however, makes Chinese intervention in some forms far more likely. China has been trying to make a point about expanding its regional interests, and a Korean war might be a game changer. China’s most predictable reaction would be “not in our back yard”, with related actions, but not necessarily direct conflict. Active Chinese participation, however, could turn the conflict in to a major regional war. The more likely immediate confrontation, if any, would be a clash of the two Koreas. That could get extremely nasty, very quickly. The DPRK has what is basically a post Cold War/ Iraq War style military force, with added naval capacity. Despite the huge size of the DPRK military , South Korea has one of the most powerful and fully modern conventional military forces in the world, and it can hit back, hard, if a confrontation arises. South Korea is perfectly capable of winning a conventional war with the North on its own. That not very secret fact, however, could well bring in Chinese and Russian support. Currently, China and Russia provide a low level of support to the DPRK military, but the overall DPRK arsenal is circa 1980s. Against modern weapons, the viability of these systems in combat is highly debatable. That very lack of viability, however, is more of a problem than it looks in a war scenario. Given the obvious problems and serious risks in mounting a conventional attack, an unconventional attack is therefore far more likely. In 1950, the DPRK mounted a very effective surprise attack which drove the combined South Korean and US forces back to the very tip of the Korean peninsula. The current scenarios are completely different, though. Against a fully prepared opponent, a surprise attack by conventional forces would have to achieve miracles. Even with a huge force, there’s no getting away from the fact that South Korea is a very hard target for the DPRK. 1950 won’t happen again, but a variant, particularly a failed variant, could create a cascade of events, including super power involvement. The most likely scenario for a real war, based on the current DPRK posture and previous actions, is a dramatic action of some kind. This would have to be a direct surprise strike, on a “no going back” basis. A serious strike would definitely bring in other nations, in different capacities. Whether the US is moving to a less engaged role or not, it has 28,000 military personnel in South Korea, and they’re potential targets either directly or as collateral damage in a strike on Seoul. Any strike on American forces, however, would instantly bring in US forces, and retaliation. The range of possible escalations is obvious. The DPRK can’t necessarily count on support in a dramatic strike, either. Starting a large scale regional war wouldn’t go down too well with China or Russia. This is no longer 1950 in other ways, too. Chinese and Russian leadership is highly pragmatic. There’s no reason to believe they’d want to be drawn in to any conflict, on any level. They are very unlikely to respond well to a sudden demand for support in a conflict with the US or Japan, or both. The degree of commitment required to support the DPRK in an actual war would be huge. Nor are they likely to enthuse about supporting the side most likely to lose in such a war. In global politics, the Koreas are a sideshow, if potentially a very ugly sideshow, if a war starts. The major powers have nothing to gain but an unwanted problem and an expensive range of options. None of those options deliver any real benefits. ICBMs or no ICBMs, the DPRK is holding one card in a game where all the other players have much stronger cards. The real risk is escalation caused by people doing the wrong things and reacting the wrong way to situations. The problem is that history is full of cases of wars starting for exactly those reasons. This opinion article was written by an independent writer. The opinions and views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily intended to reflect those of DigitalJournal.com

— The supposed development of a long range ICBM capability by North Korea has several ramifications. Whether or not the ICBM can hit the US or not, it represents a potential catalyst for a serious regional war. Sydney — The supposed development of a long range ICBM capability by North Korea has several ramifications. Whether or not the ICBM can hit the US or not, it represents a potential catalyst for a serious regional war. At this point, the US is skeptical of North Korea’s actual capabilities. There’s some doubt as to how far this technology has advanced, and whether it can actually deliver a warhead on target. Nor are the technical issues getting any simpler: The DPRK’s stated goal of delivering nukes from submarines, particularly the obsolete and rather undersized Whiskey and The DPRK, meanwhile, is trying to get the US to reverse its current policies of non-acceptance of it as a nuclear-armed state, by developing ICBMs, real or not. As a diplomatic position, it’s a bit hard to accept the logic. It’s also potentially suicidal, for less obvious reasons. Regional detonator? The regional implications of a new ICBM capability are significant. The DPRK’s neighbors have their own views on nations with nuclear strike capacity. China has no reason to consider this new development a threat, but Japan may see things differently. Japan has reacted very negatively to short and medium range tests near its territory. Add to this the alliance between China and the DPRK, and any conflict with Japan could bring in China. That’s not a natural scenario, though. China can pick and choose its level of participation in any conflict. One way of reminding a client state that it’s a client state is to leave it hanging in a crisis. That’s not impossible, either. Nor is Russia a natural engagement. In the 1950s, Russia aided North Korea in the Korean war in many ways, including equipping its air force with the revolutionary new MIG 15s which basically rewrote air tactics for the next 50 years. It’s not clear whether the Russian Federation would respond at all in any future conflict scenario. There’s not much in it for the Russians, in terms of political or other gains. “Amused spectator” would be a likely option, unless there’s any tangible gains to be made out of a confrontation with North Korea and Western-aligned nations. A confrontation between the US and the DPRK, however, makes Chinese intervention in some forms far more likely. China has been trying to make a point about expanding its regional interests, and a Korean war might be a game changer. China’s most predictable reaction would be “not in our back yard”, with related actions, but not necessarily direct conflict. Active Chinese participation, however, could turn the conflict in to a major regional war. The more likely immediate confrontation, if any, would be a clash of the two Koreas. That could get extremely nasty, very quickly. The DPRK has what is basically a post Cold War/ Iraq War style military force, with added naval capacity. Despite the huge size of the That not very secret fact, however, could well bring in Chinese and Russian support. Currently, China and Russia provide a low level of support to the DPRK military, but the overall DPRK arsenal is circa 1980s. Against modern weapons, the viability of these systems in combat is highly debatable. That very lack of viability, however, is more of a problem than it looks in a war scenario. Given the obvious problems and serious risks in mounting a conventional attack, an unconventional attack is therefore far more likely. In 1950, the DPRK mounted a very effective surprise attack which drove the combined South Korean and US forces back to the very tip of the Korean peninsula. The current scenarios are completely different, though. Against a fully prepared opponent, a surprise attack by conventional forces would have to achieve miracles. Even with a huge force, there’s no getting away from the fact that South Korea is a very hard target for the DPRK. 1950 won’t happen again, but a variant, particularly a failed variant, could create a cascade of events, including super power involvement. No good scenarios for any Korean conflict. The most likely scenario for a real war, based on the current DPRK posture and previous actions, is a dramatic action of some kind. This would have to be a direct surprise strike, on a “no going back” basis. A serious strike would definitely bring in other nations, in different capacities. Whether the US is moving to a less engaged role or not, it has 28,000 military personnel in South Korea, and they’re potential targets either directly or as collateral damage in a strike on Seoul. Any strike on American forces, however, would instantly bring in US forces, and retaliation. The range of possible escalations is obvious. The DPRK can’t necessarily count on support in a dramatic strike, either. Starting a large scale regional war wouldn’t go down too well with China or Russia. This is no longer 1950 in other ways, too. Chinese and Russian leadership is highly pragmatic. There’s no reason to believe they’d want to be drawn in to any conflict, on any level. They are very unlikely to respond well to a sudden demand for support in a conflict with the US or Japan, or both. The degree of commitment required to support the DPRK in an actual war would be huge. Nor are they likely to enthuse about supporting the side most likely to lose in such a war. In global politics, the Koreas are a sideshow, if potentially a very ugly sideshow, if a war starts. The major powers have nothing to gain but an unwanted problem and an expensive range of options. None of those options deliver any real benefits. ICBMs or no ICBMs, the DPRK is holding one card in a game where all the other players have much stronger cards. The real risk is escalation caused by people doing the wrong things and reacting the wrong way to situations. The problem is that history is full of cases of wars starting for exactly those reasons. The development of the ICBMs has now reached at least the point at which North Korea (correct name Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, DPRK) is prepared to do some gloating. While the usual pattern of information from the DPRK is based on a degree of spin, this is a bit different. When it comes to ICBMs, you either have this capacity or you don’t. So it’s likely that at least some level of increased capacity has been achieved. At this point, the US is skeptical of North Korea’s actual capabilities. There’s some doubt as to how far this technology has advanced, and whether it can actually deliver a warhead on target. Nor are the technical issues getting any simpler: The DPRK’s stated goal of delivering nukes from submarines, particularly the obsolete and rather undersized Whiskey and Romeo class subs, is of equally dubious value and almost zero combat credibility. Those subs could be tracked from one side of the Pacific to the other by Radio Shack level equipment, let alone American and Japanese ASW capabilities. A few drones could stooge around the Sea of Japan and sink them quite easily, too. Sub launched missiles really are not a working option. The DPRK, meanwhile, is trying to get the US to reverse its current policies of non-acceptance of it as a nuclear-armed state, by developing ICBMs, real or not. As a diplomatic position, it’s a bit hard to accept the logic. It’s also potentially suicidal, for less obvious reasons. The regional implications of a new ICBM capability are significant. The DPRK’s neighbors have their own views on nations with nuclear strike capacity. China has no reason to consider this new development a threat, but Japan may see things differently. Japan has reacted very negatively to short and medium range tests near its territory. Add to this the alliance between China and the DPRK, and any conflict with Japan could bring in China. That’s not a natural scenario, though. China can pick and choose its level of participation in any conflict. One way of reminding a client state that it’s a client state is to leave it hanging in a crisis. That’s not impossible, either. Nor is Russia a natural engagement. In the 1950s, Russia aided North Korea in the Korean war in many ways, including equipping its air force with the revolutionary new MIG 15s which basically rewrote air tactics for the next 50 years. It’s not clear whether the Russian Federation would respond at all in any future conflict scenario. There’s not much in it for the Russians, in terms of political or other gains. “Amused spectator” would be a likely option, unless there’s any tangible gains to be made out of a confrontation with North Korea and Western-aligned nations. A confrontation between the US and the DPRK, however, makes Chinese intervention in some forms far more likely. China has been trying to make a point about expanding its regional interests, and a Korean war might be a game changer. China’s most predictable reaction would be “not in our back yard”, with related actions, but not necessarily direct conflict. Active Chinese participation, however, could turn the conflict in to a major regional war. The more likely immediate confrontation, if any, would be a clash of the two Koreas. That could get extremely nasty, very quickly. The DPRK has what is basically a post Cold War/ Iraq War style military force, with added naval capacity. Despite the huge size of the DPRK military , South Korea has one of the most powerful and fully modern conventional military forces in the world, and it can hit back, hard, if a confrontation arises. South Korea is perfectly capable of winning a conventional war with the North on its own. That not very secret fact, however, could well bring in Chinese and Russian support. Currently, China and Russia provide a low level of support to the DPRK military, but the overall DPRK arsenal is circa 1980s. Against modern weapons, the viability of these systems in combat is highly debatable. That very lack of viability, however, is more of a problem than it looks in a war scenario. Given the obvious problems and serious risks in mounting a conventional attack, an unconventional attack is therefore far more likely. In 1950, the DPRK mounted a very effective surprise attack which drove the combined South Korean and US forces back to the very tip of the Korean peninsula. The current scenarios are completely different, though. Against a fully prepared opponent, a surprise attack by conventional forces would have to achieve miracles. Even with a huge force, there’s no getting away from the fact that South Korea is a very hard target for the DPRK. 1950 won’t happen again, but a variant, particularly a failed variant, could create a cascade of events, including super power involvement. The most likely scenario for a real war, based on the current DPRK posture and previous actions, is a dramatic action of some kind. This would have to be a direct surprise strike, on a “no going back” basis. A serious strike would definitely bring in other nations, in different capacities. Whether the US is moving to a less engaged role or not, it has 28,000 military personnel in South Korea, and they’re potential targets either directly or as collateral damage in a strike on Seoul. Any strike on American forces, however, would instantly bring in US forces, and retaliation. The range of possible escalations is obvious. The DPRK can’t necessarily count on support in a dramatic strike, either. Starting a large scale regional war wouldn’t go down too well with China or Russia. This is no longer 1950 in other ways, too. Chinese and Russian leadership is highly pragmatic. There’s no reason to believe they’d want to be drawn in to any conflict, on any level. They are very unlikely to respond well to a sudden demand for support in a conflict with the US or Japan, or both. The degree of commitment required to support the DPRK in an actual war would be huge. Nor are they likely to enthuse about supporting the side most likely to lose in such a war. In global politics, the Koreas are a sideshow, if potentially a very ugly sideshow, if a war starts. The major powers have nothing to gain but an unwanted problem and an expensive range of options. None of those options deliver any real benefits. ICBMs or no ICBMs, the DPRK is holding one card in a game where all the other players have much stronger cards. The real risk is escalation caused by people doing the wrong things and reacting the wrong way to situations. The problem is that history is full of cases of wars starting for exactly those reasons. This opinion article was written by an independent writer. The opinions and views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily intended to reflect those of DigitalJournal.com

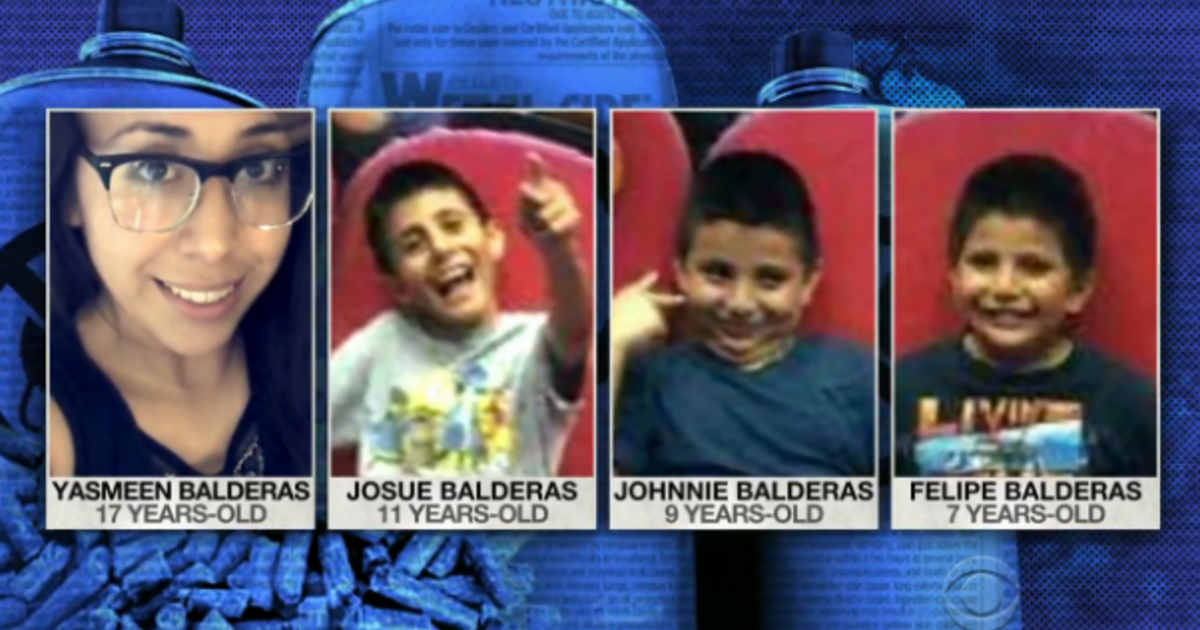

An investigation is underway into a deadly leak of highly poisonous gas in a Texas home. Four children were killed and six other family members w…

An investigation is underway into a deadly leak of highly poisonous gas in a Texas home. Four children were killed and six other family members w…

WASHINGTON (WUSA9) — There’s a host of items you should keep at home if you’re vying for a spot to watch Donald Trump swear in as the United States’ 58th president on January 20.

WASHINGTON (WUSA9) — There’s a host of items you should keep at home if you’re vying for a spot to watch Donald Trump swear in as the United States’ 58th president on January 20.