Is scoring your sleep worth paying for?

We spend a third of our lives asleep, so we all know how important sleep is, but are we doing it right? With the new year approaching, and ‘get more sleep’ an oft-heard resolution, you need to know the best way technology can help you do that.

We spend a third of our lives asleep, so we all know how important sleep is, but are we doing it right? With the new year approaching, and ‘get more sleep’ an oft-heard resolution, you need to know the best way technology can help you do that.

There are currently three ways of learning about – and improving – your sleep patterns, in ascending order of cost.

One is to download a free ‘movement tracker’ app on your phone and record yourself sleeping; a second is to use an activity tracker, and the third is to go for a full-on dedicated sleep-monitoring device.

To compare these options we pitted the SleepBot app (which promises to track your sleep through external monitoring) against the Jawbone UP3 activity tracker (which claims to measure sleep duration and quality, and adds a heart rate sensor and an Automatic Sleep Detection feature) against a third (and particularly intriguing) device: a sensor attached to the bed itself.

Called Beddit, it claims to track your sleep, of course, but also includes heart rate and breathing stats.

We put all three products on test for a fortnight to make a fair comparison. Ready, steady, sleep!

First comes the hardware set-up. Jawbone was charged up and slapped on my wrist. A slightly confusing process of pairing then ensues; I gave the accompanying UP app a lot of personal details (weight, height, age, etc) and even permission to use data from the Health app on my iPhone, but at the end I’m not convinced the wearable is funnelling data to it.

Ditto the Beddit; after peeling off an adhesive strip and sticking the 60cm-long tape to my mattress (along with a cable that plugs into a nearby socket), the Bluetooth pairing is so fast that I’m not sure if it’s successfully paired with my phone.

However, a quick lie down gives me a handy ‘live’ readout of my movement on the Beddit app. With SleepBot downloaded to my phone and having logged in and signed up, I’m all set for sleep.

After all that prep, it’s merely a case of firing up all three apps and physically telling them I’m about to go to sleep. That’s fair enough for the SleepBot app and the Jawbone UP3, but surely the Beddit knows I’m in bed?

After being woken up by my cat in early morning, and having a restless last 30 minutes of sleep, I reach for my phone the next morning and tell all three apps that I’m awake. My phone immediately shuts down, empty of battery. Well, that was close.

Once recharged, the results from all three devices are surprisingly different. The Jawbone UP3 tells me I took 10 minutes to fall asleep, slept for 7 hours and 18 minutes, had a resting heart rate of 51bpm, had deep sleep for one hour and 19 minutes, and a mere 18 minutes of less deep REM (rapid eye movement sleep).

The Beddit app agreed on the heart rate, but registered just six hours and 48 minutes of sleep. However, the results are more in-depth, as you would expect from a one-trick wearable.

As well as a ‘sleep score’ of 68/100 and a 90% efficiency rating (I understand neither, but didn’t have the best night’s sleep, so it seems fair), Beddit detected the same average heart rate, but produced a graph that tracks it slowing from 56bpm when I fell asleep to 46bpm just before waking.

It also detected four times I’d woken up, and ‘significant amounts of snoring’ at 55 minutes total, but offers few other details.

The Sleepbot app records seven hours and 36 minutes of sleep, which was the total time I was in bed. That’s it. If that seems far too simplistic, it’s mostly my fault; as well as forgetting to hit the ‘track motion’ and ‘record sound’ buttons, I left my phone on the bedside table, when I should have left it on the bed itself.

Worse, I did it again the next night; bedtime is not the best time for in-depth gadget admin.

On my third night of testing, Sleepbot was armed correctly, but everything else went wrong. I just couldn’t tell if the Beddit strap was talking to the app; it needs to send some kind of reassuring message.

However, the real problem was the Jawbone UP3; try as I might, I just could not get the app to put the band into sleep mode. Bear in mind I’m lying in bed here, and with every failed attempt, the band buzzes loudly.

After seven attempts I’m ready to take it off and fling it out of an open window, but it pairs just in time to avoid my wrath.

The next morning the Beddit app tells me that I ‘took a long time to go to sleep’. Err, yup. The Jawbone then fails to recognise that I’ve woken and am moving about. You’d think an activity tracker might be able to figure that one out for itself.

It’s the same problem with Beddit, which sounds a bizarre alarm (bamboo pipes and synthesisers?) a clear hour after I’ve risen. Is it a motion sensor, or isn’t it? Beddit even stopped recording my sleep somewhere around 2:30am one night.

Was I so still that it thought I’d left the bedroom? I put both into manual mode; the auto-detect features are plain unreliable.

In contrast, Sleepbot excelled itself. Okay, so I told it exactly when I was about to go to sleep and exactly when I woke up, but I knew where I was with it.

It also produced a detailed graph showing my light and deep sleep, and a harrowing audio log of the sound of me snoring.

And that’s not mentioning the buzzing gadgets at bedtime. My poor wife.

Teething problems over, the second week was all about collecting sleep data and seeing how the apps work.

Beddit continues to be patchy; it records heart rate in excruciating detail, but what can I do with that information? Ditto the breaths per minute.

The app offers advice on snoring (put a tennis ball down your pyjamas, apparently), but really, there are no trends identified, or any kind of personalised advice.

There’s also one massive drawback to Beddit; you can’t take it with you. During the two weeks I stayed in a hotel and at a friend’s house, so lost two days data right there.

The Jawbone tries to get involved with tips and hints on sleep (and a lot more besides), but it doesn’t understand me. I’m a night owl, I’m always awake at midnight. So receiving a message at 00:01 advising me what time I should go to bed the following night is just weird.

The app also proved buggy; it was taking correct sleep data from the device, but telling me I had slept for 19 hours and 37 minutes. I even managed over 25 hours one night! I deleted and reinstalled the app, and the problem was fixed.

I also got to like the ‘smart coach’ messages after a while, which did give advice on focusing first on sleep duration, and then working on keeping consistent sleep patterns. There is a decent stab at improving sleep patterns, though there’s also a lot of unnecessary extra info; the social media-style user interface is all a bit childlike, too.

There are other drawbacks. The UP3 lasts only five days between charges, which doesn’t compare well to the fit-and-forget Beddit, and it has to be removed every time you take a shower or go swimming, two things I do pretty frequently.

However, you can take it anywhere, and it also auto-detected an unplanned 90-minute snooze on the sofa, which the others devices can’t match.

It may be the least ambitious of the lot, but the SleepBot app proved both the most reliable and useful sleep tracker.

This app may not have any way to measure my heart rate, but it does have something that both physical devices lack; access to my phone’s microphone. Apparently I’m a bad snorer, and that was really useful to know.

Since it was the only tracker that was consistent, I trusted it. SleepBot taught me that I tend to sleep for quite different lengths over a week, thanks to its simple graph, ‘sleep debt’ figure and nightly goal. By the end of the week, I’m two hours down on what I should have had. I also get to listen to myself snore…

In short, no. Heart rate is a relatively new metric to come to life-logging, and both the Jawbone UP3 and Beddit have sensors to measure your heart’s beats-per-minute. What do they do with that information? Not much.

The automatic sleep-sensors for both failed to impress, and while the Jawbone needs regular charges, the Beddit is not good if you travel a lot.

It’s the coaching side that needs to be improved on all devices — if a device is going to collate all this data, the user wants to know what can be done with it.

After all, these trackers are bought to know if we’re having bad nights of sleep — and if so, we want to know what to do about it.

So while SleepBot may lack heart rate monitoring, and perhaps not be as super-accurate, it’s was the app that I trusted most; it proved the best trade-off between data collected and annoyance caused.

It was also free — so it’s great as long as you don’t mind having your phone on the bed with you.

Do expensive sleep trackers have a future in the bedroom? I’m not convinced. Let me sleep on it.

© Source: http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/techradar/allnews/~3/4dpHBtpURu4/is-scoring-your-sleep-worth-paying-for

All rights are reserved and belongs to a source media.

SHANGHAI: China has recovered 2.3 billion yuan (US$331.27 million) in losses from graft in the first 11 months of this year from across more than 70 different regions and countries, the country’s corruption watchdog said on its official website on Saturday.

SHANGHAI: China has recovered 2.3 billion yuan (US$331.27 million) in losses from graft in the first 11 months of this year from across more than 70 different regions and countries, the country’s corruption watchdog said on its official website on Saturday.

SHANGHAI: One of China’s top coal-producing provinces has vowed to slash its level of fine particle pollution by one-fifth by 2020, the official Xinhua news agency reported on Saturday, citing the provincial government.

SHANGHAI: One of China’s top coal-producing provinces has vowed to slash its level of fine particle pollution by one-fifth by 2020, the official Xinhua news agency reported on Saturday, citing the provincial government.

CHINA’S military has become alarmed by what it sees as U. S. President-elect Donald Trump’s support of Taiwan and is considering strong measures to prevent the island from moving toward independence, sources with ties to senior military officers said.

CHINA’S military has become alarmed by what it sees as U. S. President-elect Donald Trump’s support of Taiwan and is considering strong measures to prevent the island from moving toward independence, sources with ties to senior military officers said.

State broadcaster Central China Television has rebranded its international networks and digital presence under the name China Global Television Network as part of a push to consolidate its worldwide reach.

State broadcaster Central China Television has rebranded its international networks and digital presence under the name China Global Television Network as part of a push to consolidate its worldwide reach.

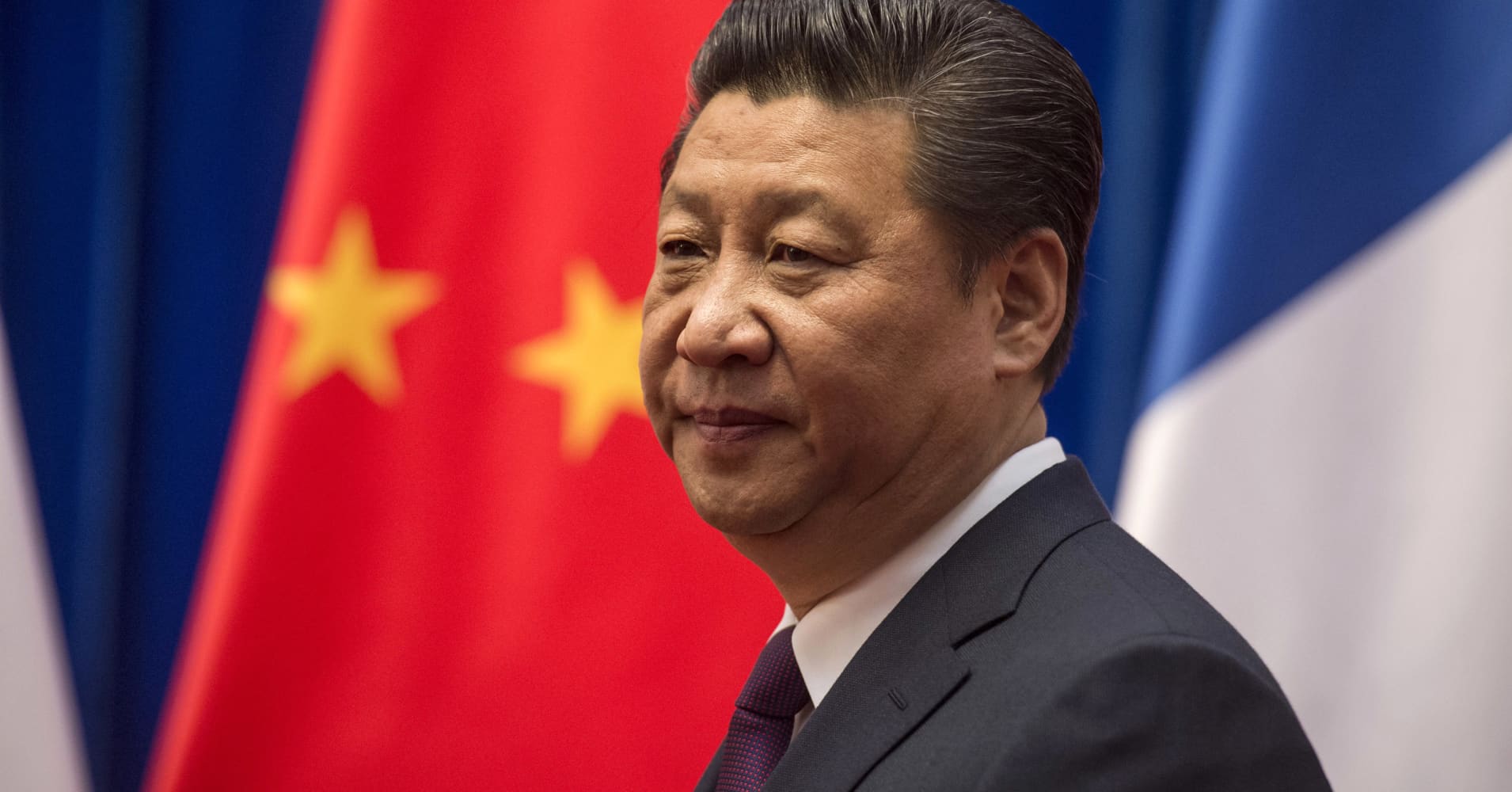

Chinese President Xi Jinping said Saturday that his government would continue to focus on poverty alleviation at home and resolutely defending China’s territorial rights on the foreign front.

Chinese President Xi Jinping said Saturday that his government would continue to focus on poverty alleviation at home and resolutely defending China’s territorial rights on the foreign front.

China will ban all domestic ivory trade within the country by the end of 2017, the country’s announced Friday, in a “game-changing” move that wildlife campaigners say may help protect the species against poachers. This move is significant for the world’s elephant population, as conservationists estimate that are killed by poachers each year, mostly to satisfy the demand for ivory products in Asia —. A published in September showed that the savannah elephant population has declined 30% in the past seven years, mostly due to poaching. The survey placed the number of wild elephants on the continent at just less than 400,000. The first phase of China’s ivory trade ban will be implemented by the end of March, when the government begins the process of shutting down the country’s 34 processing facilities and 143 designated ivory trading venues. In , an official with the State Forestry Administration said that “dozens” of these organizations will be closed by April 1, 2017. The Chinese Ministry of Culture will assist employees of the ivory trade in finding new occupations that utilize their carving skills, likely in antique restoration and maintenance. Per the directive, China will also step up its enforcement of illegal ivory sales and set up a system to regulate the transfers or sales of those ivory goods currently owned by citizens. All domestic processing and trading of ivory will be shut down by Dec. 31, 2017. Animal welfare and conservation groups worldwide are applauding China’s decision. president and CEO Carter Roberts called it “a game changer for elephant conservation”. In a press release, the Asia Director, Aili Kang wrote, “This is great news that will shut down the world’s largest market for elephant ivory. I am very proud of my country for showing this leadership that will help ensure that elephants have a fighting chance to beat extinction.” The Chinese government also plans to launch a public awareness campaign about the brutalities of the ivory trade to discourage consumers, a move through which conservation groups have seen success in China in the past. A four-year anti-ivory campaign by the International Fund for Animal Welfare — which depicted a young elephant excited about his new tusks walking with his mother — reached 75% of the urban Chinese population. showed that this specific PSA had reduced the number of Chinese people likely to purchase ivory from 54% of the population to 26%.

China will ban all domestic ivory trade within the country by the end of 2017, the country’s announced Friday, in a “game-changing” move that wildlife campaigners say may help protect the species against poachers. This move is significant for the world’s elephant population, as conservationists estimate that are killed by poachers each year, mostly to satisfy the demand for ivory products in Asia —. A published in September showed that the savannah elephant population has declined 30% in the past seven years, mostly due to poaching. The survey placed the number of wild elephants on the continent at just less than 400,000. The first phase of China’s ivory trade ban will be implemented by the end of March, when the government begins the process of shutting down the country’s 34 processing facilities and 143 designated ivory trading venues. In , an official with the State Forestry Administration said that “dozens” of these organizations will be closed by April 1, 2017. The Chinese Ministry of Culture will assist employees of the ivory trade in finding new occupations that utilize their carving skills, likely in antique restoration and maintenance. Per the directive, China will also step up its enforcement of illegal ivory sales and set up a system to regulate the transfers or sales of those ivory goods currently owned by citizens. All domestic processing and trading of ivory will be shut down by Dec. 31, 2017. Animal welfare and conservation groups worldwide are applauding China’s decision. president and CEO Carter Roberts called it “a game changer for elephant conservation”. In a press release, the Asia Director, Aili Kang wrote, “This is great news that will shut down the world’s largest market for elephant ivory. I am very proud of my country for showing this leadership that will help ensure that elephants have a fighting chance to beat extinction.” The Chinese government also plans to launch a public awareness campaign about the brutalities of the ivory trade to discourage consumers, a move through which conservation groups have seen success in China in the past. A four-year anti-ivory campaign by the International Fund for Animal Welfare — which depicted a young elephant excited about his new tusks walking with his mother — reached 75% of the urban Chinese population. showed that this specific PSA had reduced the number of Chinese people likely to purchase ivory from 54% of the population to 26%.